True Grit: KTM X-Bow takes on the Dubai 24hrs

Meet the team that's battling more than just the clock...

The Dubai Autodrome was once envisaged as the beating heart of Motor City, a lavish development intended to bestow the oil-rich region with an international motorsport destination that combined a world-class circuit with homes, hotels and, among other things, a theme park.

But shockwaves from the global economic downturn of nearly a decade ago rocked even these parts, and though some construction continues today, much of the proposed work ground to a halt. Far from reflecting the wealth of the neighbouring metropolis, the abandoned relics that overshadow the track have more in common with Dubai’s barren desert lands, evidence of which often cascades across the asphalt.

Words: Joe Holding

Photography: Joel Kernasenko

This is an extended version of a feature which first appeared in Issue 293 of Top Gear Magazine.

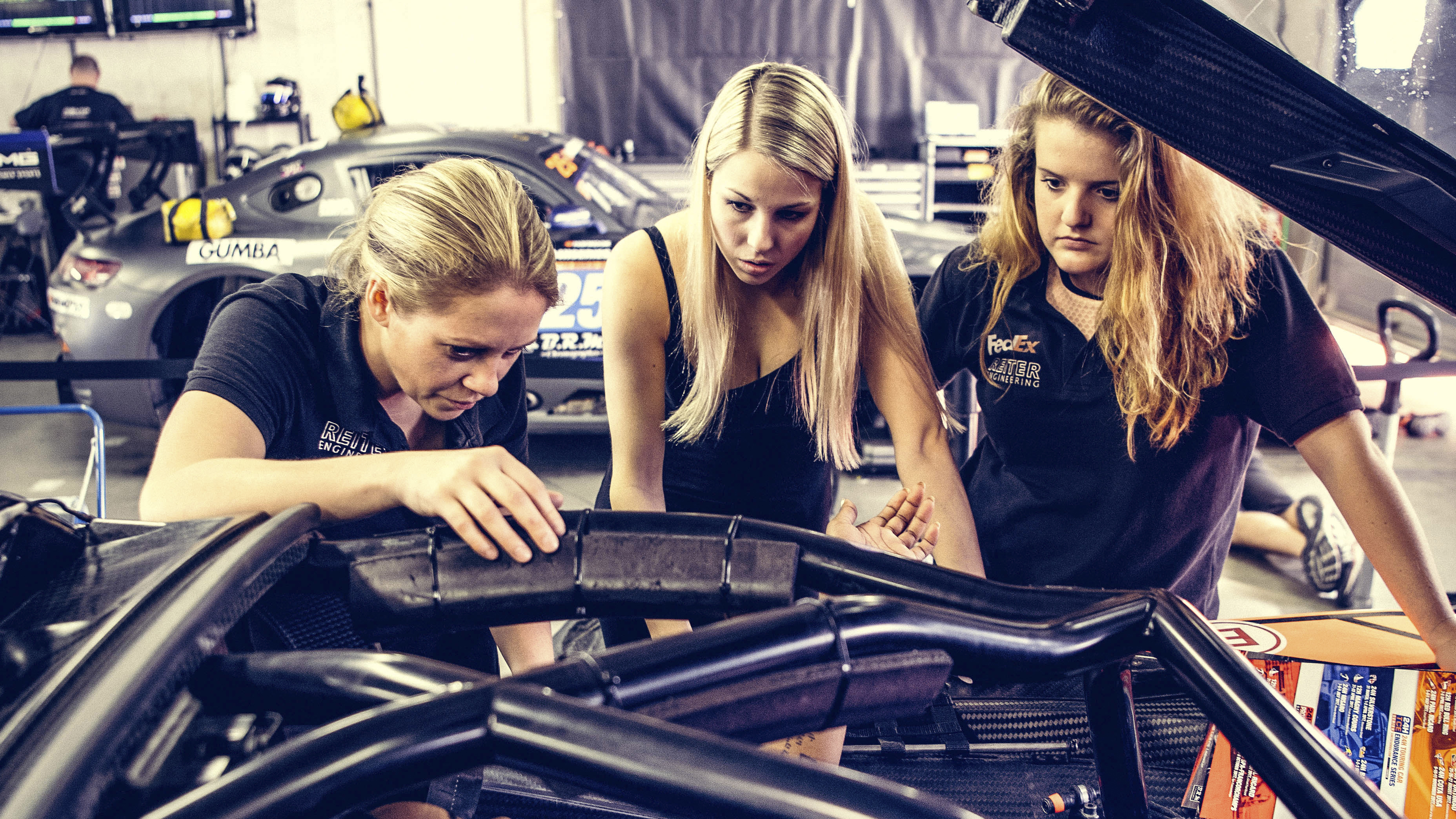

An unfulfilled dream the complex may be, but it’s where Caitlin Wood, Naomi Schiff, Marylin Niederhauser and Anna Rathe are intent on pursuing theirs. Assembled by Reiter Engineering for a tilt at this year’s Dubai 24 Hour, the all-female team has high hopes of taking its race-ready, 355bhp KTM X-Bow to a class podium. Rival GT4s, beware.

But amid the flurry of photo and autograph requests in the minutes prior to the race, even supportive onlookers can be seen raising eyebrows and heard uttering variations of “Wow, that girls’ team is quick.” Naomi, already a veteran of day-long races at Spa and Zolder, has heard worse before now: “I’ve also had people come up to me and say, ‘There’s no space for women in motorsport – just give it up.’ It adds fuel to a fire which is already burning.”

There’s no escaping the common perception that women are physically less suited to racing than men, but when it comes to motivation, the similarities between the sexes are irrefutable. Naomi found her passion for racing at a friend’s birthday party at the age of eleven, karting at a track in South Africa. Displaying a natural aptitude for speed, she begged her dad to take her back for another go, as so many boys that age do. Within a year she was winning junior events.

Caitlin – raised in Newcastle, Australia – began in karts too, hooked in by a sibling rivalry at the age of seven thanks to a brother who was likewise destined for a future in motorsport. And Swiss native Marylin also discovered a passion for racing via her family, catching the “virus” from her father and brother-in-law in her early teenage years. It’s an illness that doesn’t discriminate between genders.

The final piece in Reiter and KTM’s jigsaw in Dubai is Anna, whose journey differs significantly to those of her younger teammates. A farmer and veterinarian by trade, an “early midlife crisis” made her realise that she “needed something else but work” after turning 30. Initially that something was a Nissan GT-R, which remains her daily driver, but at 35, racing is what gives her “the best feeling in the world”.

As a dedicated feminist she is determined to prove that women can perform just as well as men on the racetrack, although that’s a daunting challenge when participation figures are so low across the board. In the UK alone the Motor Sports Association estimates that only four per cent of racing licence holders are female, and that the number of active racers could be lower still.

Contemplating this imbalance, Anna observes that driving is often established as a masculine activity from a very early age: “If you are a family, and every single time you go to the grocery store dad is the one driving the car, that becomes normal for the children. In my opinion that is what creates the difference.”

The vet-turned-racer is convinced that the problem is environmental and not genetic, and that a change in attitudes would lead to more women competing at an elite level. “Girls need to see other girls racing,” she says. “The boys so naturally all the time get positive feedback on them going racing. But the girls need the same. We just have to start getting more girls into racing.”

Easier said than done, but that isn’t to say nobody is trying. Hans Reiter – founder of the team that bears his name – wound up in racing entirely by accident after completing his engineering studies, proclaiming that the profession was “the only legal drug”. In between hits he has spent his career searching for every competitive edge, and in the shape of the girls he believes he has unearthed another performance gain.

Top Gear

Newsletter

Thank you for subscribing to our newsletter. Look out for your regular round-up of news, reviews and offers in your inbox.

Get all the latest news, reviews and exclusives, direct to your inbox.

“Women are typically light,” he explains. “The men are 80, 90, 100 kilos. This is a disadvantage of half a second, which in racing is not compensated. Women should have an advantage in long distance, and I want to prove it.”

Let the experiment begin.

***

On her penultimate day as a teenager, 19-year-old Caitlin is tasked with navigating through the bedlam of the rolling start, having guided the X-Bow to 55th place on a whopping grid of 92 starters, eighth in the SP3-GT4 category.

While the first laps require a cool head and supreme spatial awareness, at no point does that stop being the case. For 24 hours. And with everything from supercharged touring cars to monstrous GT3s continually plunging into corners three or more abreast, Zen-like concentration is essential at all times.

In the garage, Caitlin’s mum Marianne keeps a keen eye on the timing screens. All her children raced, she says with a pronounced sigh, and the maternal worry never subsides. But while her daughter’s safety is always of concern, her performance certainly isn’t: Caitlin, finding her rhythm, sets a personal best of 2:10.637 to go second fastest in class, with the only blight on her stint being a loose piece of bodywork that forces an unplanned pitstop. Gaffer tape deployed, problem solved. So far so good.

One hour and forty-six minutes into the race, Anna steps up to take over at the wheel. Her participation might be recreational, but that doesn’t diminish the immense the weight resting on her shoulders. “The risk of failing is big,” she admits, and having struggled to match the pace of her teammates in practice, she knows their chances of success hinge on her getting up to speed. “Racing is all in your head. When I am smiling and confident, that’s when I perform at my best. And it shows in the lap times.”

With that in mind, the engineers agonise over the telemetry as Anna ventures out onto the circuit. On cold tyres she begins cautiously, wary of both the lack of grip and the restricted vision from inside the cockpit. But as the rubber wears in she begins to find tenths, and before too long those tenths have become three-, then four-, then five-second gains. Up to sixth in class, the farmer is ploughing through the field.

Making way for Marylin, even Anna’s full-face helmet can’t conceal a beaming smile. “That was like the best hour ever,” she enthuses. “You have no idea how much fun it is out there.” The effect on the rest of the team is tangible. It might be getting dark, but with all drivers now firing on all cylinders, everyone’s eyes have lit up. That podium finish is well and truly on...

You hear crashes immediately at the Dubai 24 Hour. In the event of an accident, the stewards can neutralise the race by issuing a Code-60, which, via the means of a purple flag, compels all cars to slow down to a steady 40mph. It has the effect of suddenly lowering the noise levels throughout the circuit, and the drops in volume are a constant source of anxiety as teams pray it isn’t their car in the barriers.

At 17:36 – just over three and a half hours after the start of the race – one such order is lifted following a 40-minute delay, but seconds later it’s back in force. Something has gone wrong at the restart. Voices hush in the KTM garage as the TV camera pans through the haze to pick out a crippled Porsche 991, a mangled BMW M3... and a familiar orange X-Bow. An outburst of groans shatters the silence. Disaster.

The damage is severe. Naomi reckons 80 per cent of the rear needs replacing, and a complete fix will take the best part of three hours. Consoled by her teammates, Marylin recalls how the car ahead lost power the moment the green flags appeared. Swerving to avoid a certain collision, she became a passenger in another, and with it those podium dreams vanished.

The highs and lows that follow underline why it’s called “endurance racing”. Robbed of the chance to drive with something to compete for, Naomi grits her teeth and shows strong night pace which suggests the newly-repaired car is injury-free as the clock ticks past 10pm, but with Marylin back at the wheel the team is dealt another cruel blow. Rapidly losing grip on an aging set of tyres, the Formula 4 graduate makes an error which leaves the battered X-Bow in the wall. “That’s motorsport,” shrugs Caitlin. Naomi agrees: “It’s brutal.”

For most, this would be enough to call it a day, but Hans insists that the car must be repaired again so the girls can experience as much track time as possible. The mechanics – already deprived of sleep before the race – muster the strength for another big rebuild. A Herculean effort gets the car back on the road some five hours later, an endeavour fuelled by an unshakable belief in what the girls are capable of.

Emerging into the break of dawn, the team finally starts to log consistent laps, albeit covering ground that their SP3-GT4 rivals ticked off many hours earlier. Though out of the running the girls push on regardless, and eventually their persistence is rewarded with an on-track pass on the class-leading Optimum Motorsport entry. After the misfortune of the previous evening, outpacing the Ginetta G55 is a welcome victory, even if it’s merely a consolation prize.

***

Come the chequered flag, the end result – last but one of the 73 classified finishers and 195 laps down on the class winners – disguises not just the team’s potential, but the depth of their efforts as well. Mentally exhausted even with the long periods in the garage, the team has borne some physical damage via a crash-induced pain in Marylin’s leg, though she insists “it’s nothing”.

“The pace is there, it’s just bad luck,” rues Anna, echoing Naomi’s fears that it will “look so much worse” because they are all female. “Which is totally unfortunate because it shouldn’t be that way. There have been so many cars out there which have had the same incidents. Our impacts were just too big to repair quickly.”

“We didn’t really prove the point about women,” Anna concedes. “So maybe someone else can. Someone has to try.”

What a watershed moment for women in motorsport looks like is anyone’s guess, but perhaps with more examples of the kind of backing afforded to this team by KTM and Reiter Engineering, it would happen a lot sooner. If only for the sake of giving girls and boys an equal opportunity to enjoy the thrill of racing, the earlier, the better.

Trending this week

- Car Review

BMW 1 Series