Alpine A110 chases its past

Alpine is back. We take the new A110 to follow in the footsteps of a legend

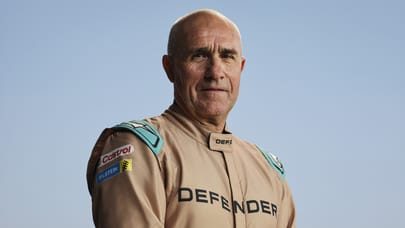

“I won because the A110’s agility and lightness made up for the lack of power”

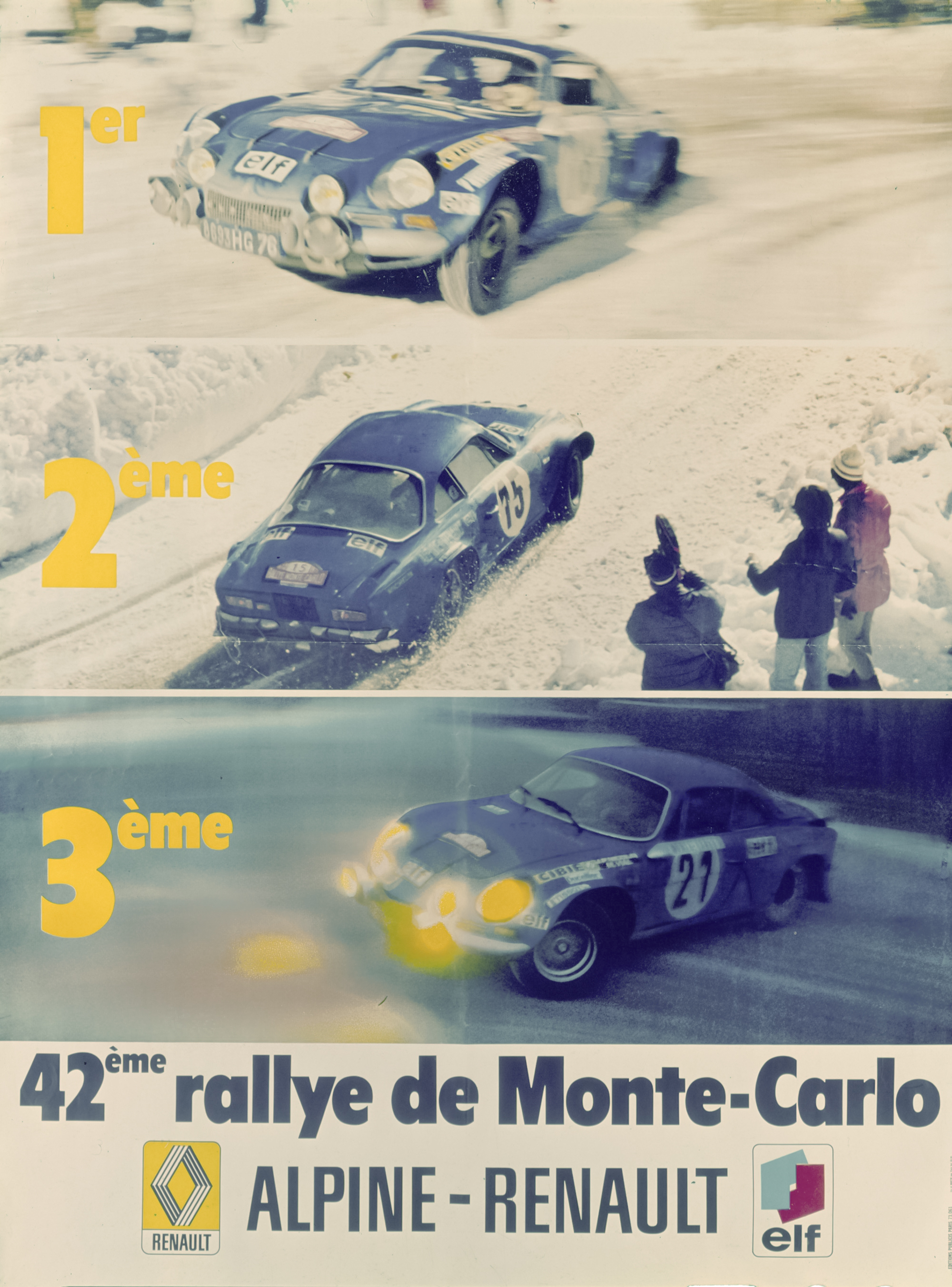

In 1973, Jean-Claude Andruet won the Monte Carlo rally in an original Alpine A110. Forty-five years later, we’re on those same stages in its successor. The reasoning is simple. Renault has brought Alpine back because it believes sports cars are going wrong. They’re too heavy, caught in a vicious circle of power and weight gain. The new A110 is different – the vicious circle turned virtuous.

This car weighs 1,103kg. That’s full of fluids, no cheating, promises Thierry Annequin, the chassis technical leader, “because to us a kilo is 1,000 grammes”.

So, having not made a car for over 20 years, Alpine is back – and staying pure to the ideology laid down by the firm’s founder, Jean Rédélé, and successfully proven in competition by Jean-Claude Andruet. And we’re going to put it to the test on the roads that forged the A110’s reputation – a virtuous circle of our very own.

Words: Ollie Marriage/ Photos: Mark Riccioni

But first we have to get there. That takes several hours and a very deliberate route choice from Alpine’s launch base near Aix-en-Provence. The satnav will tell you to take the A8 to Menton and hang a left. Ignore it. Instead join the dots that link Manosque, Digne, Saint-Julien-du-Verdon, Entrevaux and Duranus. It is close to car nirvana: the valleys deepen, the scenery builds, the roads are unable to stamp their authority on the contours and gradients so start ducking and weaving. Panic-stricken by the terrain, they twist frantically and eventually coil themselves into impossible knots. Congratulations, you’ve arrived at the Col de Turini.

We left at dawn, my head churning facts and figures, most of which I find alluring, one I find alarming. Construction is all-aluminium – bodywork, chassis and suspension, which is double-wishbone all round because of the camber control it gives through the suspension’s movement. That’s needed because Alpine wanted to team light weight with soft springs. Body roll is not the enemy.

The focus on weight-saving is astonishing and not the lip service we get from so many brands (“Yes sir, a carbon roof makes all the difference”). Sabelt has developed a fixed-back chair that weighs a mere 13.1kg. They also do work for McLaren. But this is lighter than anything Woking has. Brembo has built the parking brake into the rear caliper (a world first), rather than fitting a separate one. That’s saved 2.5kg, with another kilo saved by doing away with a separate control unit. It’s all built into the Bosch ECU. And the brackets that hold the cables and hoses are aluminium: “This is unusual”, claims Annequin, “but it saves seven grammes here, 12 grammes there and it adds up.”

It’s also expensive to do. Which might explain why the Première Edition you see here, a limited run of 1,955 cars (the year Alpine was founded), will cost €58,500 (currently £51,680). I’m thinking what you’re thinking. It’s way too much. They’ve sold the initial batch already – doubtless to people who understand and appreciate the benefits of light weight. But an entry-level A110 is still going to be, what, about £45,000 in the UK? More than a Porsche Cayman or Audi TT S, both of which have more power (and more weight, and worse power-to-weight ratios, but you know how people think) and come from more established, recognised, admired brands. Like it or not, Alpine is an unknown quantity.

And the A110 isn’t balancing price against an exotic engine. It’s a 1.8-litre four-cylinder turbo shared with the new Megane RenaultSport. But, with 249bhp and 236lb ft, less powerful. And there’s no manual gearbox to coo over either. Instead a Getrag 7spd twin-clutch, sharpened up from the Clio with wet clutches.

According to MD Michael van der Sande, Alpine wanted to do both, but resource limitations meant they could choose to do two adequately, or one well. He also as good as admitted that other versions will arrive in due course (more power, different bodywork). Maybe we’ll get a manual then, too.

There are load bays front and back. The front is shallow; it won’t swallow much more than snowchains, coat and road atlas. I have to half unpack my overnight bag before it’ll squish through the rear aperture. The cabin is more roomy, but then van der Sande is six foot six. It’s an easy car to feel comfortable in. The Sabelt seats are superb in every regard, the A-pillars are a long way forwards, information is clearly presented on the dash and central touchscreen. There’s a handy phone slot, a less handy slot of a rear window. I love the central bridge, how low you sit. Not such a fan of the scratchy door plastic, and, given what Alpine is saying about the way the car drives, does it need such a thick-rimmed steering wheel? And isn’t the boss slightly off-centre?

Top Gear

Newsletter

Thank you for subscribing to our newsletter. Look out for your regular round-up of news, reviews and offers in your inbox.

Get all the latest news, reviews and exclusives, direct to your inbox.

But I like it in here, it feels different and, for a Renault, very well built. So I head out into the dark. We’ve got a long-term Cayman, and I made a point of spending a few days in it before coming out here. The Alpine’s a quieter cruiser, less road noise. No suspension noise, either, chassis is rigid – it’s calm and unassuming.

The first issue doesn’t start until I’m a few miles up the A51. It’s a light, mid-engined, RWD car with narrow-ish 205-width front tyres (mounted on 18in Fuchs alloys) and although Alpine has done well to get 44 per cent of the weight over the front axle, the A110 does get buffeted. A little by truck ruts, quite a lot by crosswinds. It’s a car that needs an attentive hand on the tiller. This or a Cayman for a long journey? This actually – the fatter-tyred Cayman’s road noise is more of an issue for me. Also the trip computer reads 37.6mpg.

And motorways are where the Alpine is at its worst… Everywhere else, its size and weight are purely beneficial. I slip quietly through a few villages, where cobbles and speedbumps are taken in a way that feels… unusual, actually. It rides over them so distantly I could almost be in the long-term Discovery we’ve got along as our crew car, were my backside not several feet nearer the ground. It’s not only uncanny, but this rounding off of sharp edges is actually really satisfying. I find myself picking out bad bits of road, potholes, manhole covers just to convince myself everything it’s done so far hasn’t been an alarming fluke.

“The Monte Carlo at that time was very snowy and icy, and when I think of it, I wonder how we managed to make it safe to the finish line.”

I know where Jean-Claude is coming from. As dawn breaks, a dramatic temperature inversion takes place; the low winter sun never penetrates into the hearts of the deepening valleys. As we wind eastwards, past the aqua blue of Lac de Castillon, we enter a world of frost and snow. On winter tyres, the Alpine remains astonishingly sure-footed. Sure, it’ll later become apparent that there’s a bit of extra squidge and mush in them when they get hot, but in this wonderland of ice and quiet they’re just the ticket.

The A110 is well suited to this environment. Left in Normal mode, it’s a hushed, supple, undemanding car. It responds gently, the 1.8 is fuss-free (and a little charisma-free, too), it’s obedient, well-mannered, but possibly a little plain. I’m enjoying its behaviour, but the enjoyment is more philosophical than heart-thumping. You have to find your own satisfaction and reward – it’s not a constant sensory bombardment.

That changes above La Bollène-Vésubie. We’re high now, and the road clings to the sides of the mountain. Sport mode alters the throttle, gearbox, steering, stability and exhaust noise. But not the dampers. They’re passive. And quite brilliantly set up.

Now, as I wriggle and writhe my way up towards the 1,607m Col de Turini, the Alpine comes alive. It’s the lack of inertia that strikes you. The A110 just flows, seems to be suspended above the surface, to glide where others would stomp. It whips around hairpins without collapsing into understeer or oversteer, and the engine seems to be pushing against an open door – it surges forward from 2,000rpm. The turbo lag I felt in Normal has largely disappeared, and certainly above 4,000rpm the response is crisp and immediate. It sounds good too – artificial, but not as pantomime as the Cayman.

And Renault is right, the double-clutch gearbox is much improved. Upshifts pop home quickly, it’s just the downshifts that are slacker, with little engine braking. Not that it matters when you have a set of brakes this potent. One of the things that’s most impressed me so far is how harmonious the A110 is, how each component has been honed and adapted to meld perfectly with every other, to exhibit the same characteristics, even. The exception is the brakes. They’re fabulously tenacious. I kind of wish the steering had this much bite, in fact…

“The race was long, unpredictable and challenging! I feared La Madone and loved the Moulinon, Burzet, Turini.”

I spend the next few hours flitting up and down the Turini. It’s a fantastic bit of road – provided you’re in something small and agile. I can’t think of much this side of a Lotus Elise that’s smaller or more agile. And that wouldn’t be such a cosy respite from the cold and wind. The Alpine never appears to work hard, even when you push hard. It remains wonderfully adjustable, placeable and accurate; it dances and skips along, highlighting all the benefits of a kerbweight that carries a quarter of a tonne less baggage than a Cayman. It is magic. I come to the conclusion there’s actually nothing I’d rather drive on this road right now. And then an old rally-prepped Porsche 911 drives past.

It’s a link back to the old Alpine world, and, in a moment of clarity, I understand why the original A110, just 720kg, was so successful here. The consequences of an off don’t bear thinking about, but in the hands of Jean-Claude Andruet I can see precisely why it did so well – a clean sweep of the podium in 1973, no less. It’s unlikely Alpine will take the new one rallying – the regulations have changed too much for it to be competitive. It’ll do its racing on circuits instead. Pity, I can’t help thinking, when it deals with these roads so efficiently and enjoyably.

So, the steering. There’s nothing wrong with the grip or way it changes direction, but I’d like the front end to bite harder and have a bit more weight. This set-up might suit the car, but it’s a little unmemorable. What a terrific achievement this car is, though. So unusual to have a company brave enough to try something different, to attempt to sell the concept of lighter weight to an audience brought up on greater power. That takes guts.

At the famous Col de Turini crossroads, I take the fourth exit, the one that leads up to the roof of the world. It seems fitting to drive a lightweight sports car somewhere the air is thinner. One of the questions I had put to Jean-Claude Andruet was whether he enjoyed driving the A110. This was his reply: “Actually I dreaded the end of the races because I had to stop driving the car; I could not get enough of it.” As I sit in this beguiling, delightful, deft, different little coupe, I know precisely what he means. The more I drive, the better it gets.

Trending this week

- Car Review

BMW 1 Series

- Top Gear's Top 9

Nine dreadful bits of 'homeware' made by carmakers