What's Toyota's one-off hydrogen fuel cell rally car like to drive?

We’re all thinking it, aren’t we? If you had the ways and means to build your own rally car, the Toyota Mirai – a 1,850kg, 152bhp hydrogen fuel cell saloon that makes the Ssangyong Rodius look like a masterpiece – might not be the first place you’d begin.

Not least because the Mirai costs 7.24 million yen (£39,000) in Japan before you even sniff a bucket seat, and can only be fueled at 27 stations across the country.

So, when Top Gear asks Mitsuhiro Kunisawa, a top Japanese auto journalist and the man who devised this project, why on earth he decided to sink his hard-earned yen into it, we maybe expected a slightly less philosophical answer.

“Why do you climb mountain?” he shot back at me, with one eyebrow raised. Right.

A little digging into Kunisawa-san’s past reveals a love and talent for rallying that spans 15 years, and lately his focus has turned to rally cars with a big twist.

“If I see a new technology, I want to drive it quickly,” he tells us.

Back in 2013, Kunisawa converted a Nissan Leaf from showroom- to rally-spec, and competed in three events in the Japanese Rally Championship 1400 class. First time out he was dead last, second time around he placed third, and third time he won it. When he says he likes to drive quickly, he isn’t lying.

All the more impressive is that his Leaf had 109bhp and weighed 1,500kg, whereas his competitors had 120bhp and just 1,000kg to haul around. The key, he tells me, is having the weight concentrated so low in the chassis, with the instant torque that’s inherent with all EVs.

And it should be a similar story with the Mirai, given it’s essentially an electric car with a small hydrogen power station on board.

Top Gear

Newsletter

Thank you for subscribing to our newsletter. Look out for your regular round-up of news, reviews and offers in your inbox.

Get all the latest news, reviews and exclusives, direct to your inbox.

Weight savings from Mirai’s stripped-out interior are cancelled out by the full Group N-spec roll cage, and the powertrain is as standard, but even so it should be marginally quicker than the Leaf: with 152bhp and 1,850kg, the Mirai’s power-to weight ratio is fractionally superior.

Time to point out the obvious: in a straight line this is not a quick car. In fact, by rallying standards, 0-62mph in 9.6 seconds is glacial. Even Top Gear’s own Hyundai i20 rally car – widely considered to be the slowest straight-line race car in the world - would out-drag it.

But as anyone with racing experience knows, it’s the corners that count and it’s here that Sanko Works – the rally specialists Kunisawa tasked with the conversion – have gone to work.

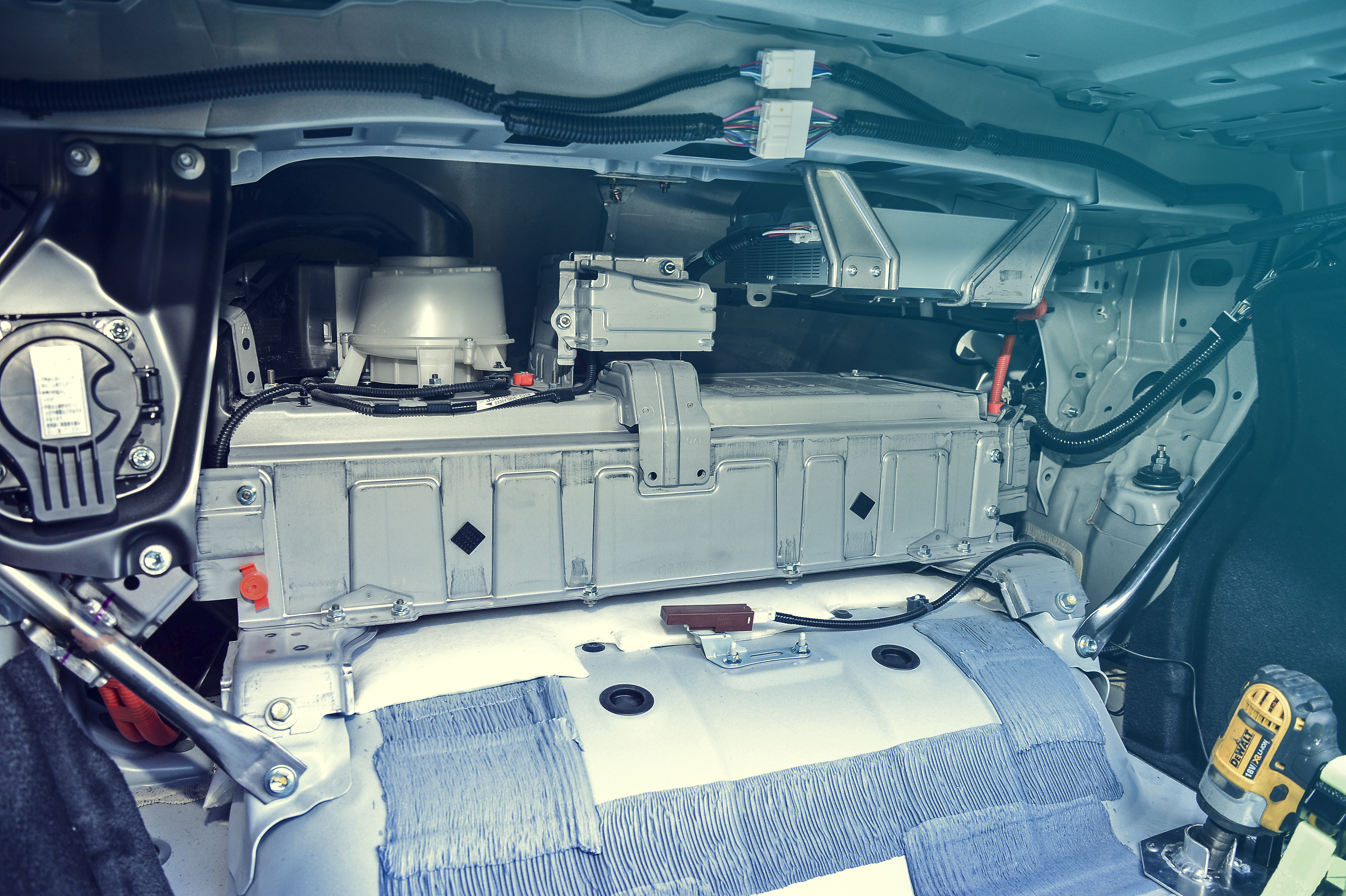

Takahiro Kitami, the chief mechanic Kunisawa refers to as his “little genius”, spent almost two months fitting the roll cage (requiring the entire dash to be removed), stripping back the interior, fixing 6kg Bride bucket seats on bespoke mounts, bolting on the comedy rear wing and fitting in-house developed springs and shocks at each corner.

The key, according to Kitama, is a flexible join between the suspension and the body that allows slight lateral as well as vertical movement – crucial considering the punishment rally cars have to absorb.

Posting myself ungracefully into the driving seat, while Kunisawa assists me with the plum-constricting four-point harness, I’m overcome with a sense of responsibility. Not just towards my unborn children, but to Kunisawa himself; this is his baby, his pet project and I’m the first person outside his inner circle to drive it.

He’s just informed me to take it easy, as the car is competing in its first-ever rally – the ninth round of the Japanese Rally Championship - in two days’ time, and he’d rather it wasn’t bent or rolled.

As luck would have it I’d driven the standard Mirai in Hamburg a week earlier, and along the meandering country roads that surround Sanko Works’ workshop in Isumi, a 90-minute drive from Tokyo, the rally car feels remarkably similar. A little louder perhaps, but there’s the same whine from the front-mounted motor and the same hum from the fuel cell doing its thing.

Ask for full power and the response from the motor, single-speed gearbox and subsequently the front tyres is just as instant, but no more frantic.

It’s not until I tip it into the first tight corner, expecting it to lollop onto the outside wheels and understeer into the nearest ditch, that the true transformation shows its face. Body roll is cut by half, maybe more, and the front end digs in harder thanks to 20 per cent softer tyres than standard.

But at the same time it’s still supple, breathing with the road surface rather than fighting and crashing against it. The net result is it moves with far less inertia, feels lighter on its feet and stops with more bite, too, courtesy of upgraded pads.

Ever wanted a lesson in the importance of conserving your momentum in corners? This car wrote the syllabus.

What I didn’t expect was rather than the lack of acceleration spoiling the experience, it simply forces you to attack it from another angle: concentrating hard, steering smoothly and picking your braking points and braking force to perfection. Do so and you can make unexpectedly brisk progress, as Kunisawa has already proved.

Back in August he made an appearance in the Mirai at the WRC Rally Germany. Officially a course car, he was given the green light to attack the Trier stage with everything he had.

The timing, although unofficial, was eye-opening – he squealed around just three seconds slower per km than the WRC S1600 class. Off the pace, but not by as much as the WRC boys would like.

How long then until we see a hydrogen WRC competitor, or even a fuel cell F1 car? Kunisawa has his theories: “The fuel cell has shrunk by 50 per cent in 5 years. If the same happens again we could have a 300bhp, lighter rally car by 2020. Then a H2 series is possible.

“In 30 years F1 will be hydrogen, too. Conventional tech has already been taken to its maximum, but fuel cell tech will only become better from now on…”

Featured

Trending this week

- Car Review

BMW 1 Series

- Top Gear's Top 9

Nine dreadful bits of 'homeware' made by carmakers