Top Gear's Bargain Heroes: the Ford Racing Puma

A super rare fast Ford for the price of a new Ka+. Ford Racing Puma buying guide here

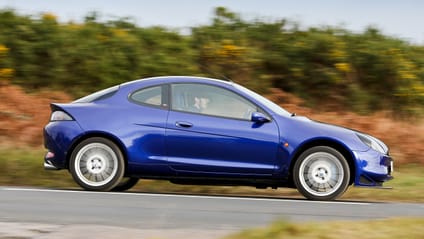

There have been many fast Fords, but I’d argue this is the oddest of the bunch. The Racing Puma – though similar in body style to privateer Puma rally cars – never technically raced. And while its body was significantly pumped-up over standard, it used the same 1.7-litre engine as standard Pumas, with only the lightest of upgrades.

It also didn’t do particularly well. Ford planned to make 1,000, cut that to 500, then still had to sell some of those internally to make sure every Racing Puma found a home. The reason? A £23,000 asking price. That would seem extortionate for a 153bhp hot hatch now, never mind in 1999. Especially when a 30bhp-lighter Puma 1.7 sold for ten grand less.

Now, the price difference is even more stark. While you can pick up scruffy but usable Puma 1.7 for under £1,000, you’ll pay six or seven times that for a similar Racing Puma.

But to boil it down to cost along is to ignore what a special car this is. Just look at it! I’ve driven few cars with better stance when they’re entirely standard. And the upside of its below-par sales new is ferocious rareness and desirability now. You’ll struggle to find another car this rare for the cheaper than a bum-basic Ford Ka...

Pictures: Adam Shorrock

Advertisement - Page continues below

What made the Puma so expensive new was the bodywork, which looks so fantastic in the pictures above. It was fitted by Tickford, and for the large part was grafted on top of the standard Puma’s panels as opposed to replacing them.

The FRP was wider than standard, its track widths are up too, while the suspension had an overhaul to make it a tauter, stiffer car than standard. The brakes were fairly hardcore, too, Alcon helping Ford develop a four-piston braking system apparently capable of over 1g of stopping force.

In comparison, the engine barely changed. While 180bhp or more had been touted, the project’s swelling costs saw this dropped to 153bhp, with the Puma’s 1.7-litre naturally aspirated engine – a fantastically revvy unit, co-developed with Yamaha – getting a remap and some cam work. There was also a new, rortier exhaust.

The interior was as special as the exterior, with some eye-catchingly blue Sparco sports seats and a blue suede steering wheel added to the Puma’s wonderfully simple cabin.

It already had some driver-focused white dials and tactile metal gearknob, and the Racing’s extras added a bit of fun. It wasn’t the last word in quality or craftsmanship, but that’s hardly ever been in the hot hatch remit.

Ford made the Racing Puma in just one spec, with all 500 sold in the UK. Though extras were available, a limited-slip differential among them. Such an unashamed, motorsport-inspired special edition would sell it before it had even been seen nowadays (the Ford Focus RS500 of 2010 is a case in point), making this Puma’s contemporary struggles appear odd.

The clamour to get hold of one now is perhaps the British buying public making up for it, nearly 18 years after the FRP’s launch…

Advertisement - Page continues belowHow it feels to drive today

Drive anything from the 1990s or early 2000s today and it’s the clarity and abundance of its feedback that’s most immediately noticeable. The Ford Racing Puma is no different. The steering is fantastic, the wheel small and hugely communicative.

The ride is very firm, and you’re jiggled about a fair bit on Britain’s bumpier B-roads. But it’s no worse than the current Fiesta ST. And I quite like a firmly sprung small car: it immediately puts you in the mood to grab it by the scruff of its neck, and that’s exactly the treatment the FRP relishes.

Its grip is seriously impressive, and it takes two corners before you’re utterly faithful in the car beneath you, and willing to drive it as quickly as you can muster.

Which is a blessing and a curse. I owned a standard Puma and loved its power-to-grip ratio; it was a fun and playful thing, but all at very sensible speeds.

The Racing Puma, in comparison, is a bit serious. It’s undoubtedly more capable than the car it’s based upon, but the improvements to its chassis far outstrip the upgrades to its engine. You end up with a car whose limits are much, much higher than before. All the more reason to drive it harder and harder, though…

And short on muscle it may be in this car, the engine is still an utter gem. It’s just a joy to rev, and it’s impossible to resist driving it everywhere like a 17-year-old who’s just torn off the L-plates. It may technically be a small coupe, but its attitude is 100 per cent hot hatch.

And while I’ve got a teenager’s mindest, I think I’d tweak my FRP to have a touch more power. Not loads, but something close to 200bhp would still be well within the chassis’s limits, but would probably liven it up quite nicely. I’m not one for modifying cars at all, but I think this Puma would shine brighter if its on-paper stats were a little bigger.

There’s so much to enjoy as standard though, its most praiseworthy element being its gearchange. The Puma’s slick, satisfying shift is one of the best I’ve ever used. Seriously. And the Alcantara steering wheel is an object of nerdy joy.

In fact, the whole car is a bit like that. Dig beneath its maxi rally car looks and its whole backstory is a geek’s dream. Perhaps my favourite nugget is that Richard Parry-Jones – the man who made late 1990s Fords so sublime to drive – decided the chassis setup should be firmer, and so a set of ‘RPJ’ dampers were made to fulfil his wish.

Actually, 20 sets were made, and for around £600, you can add one of those to yours now. Think you’d have to, wouldn’t you?

Advertisement - Page continues belowWhat to watch out for

“To get around the homologation rule what people actually bought was a standard 1.7 Ford puma with a Racing Puma option pack,” says Simon Crosby, a Racing Puma expert. “Most never saw the 1.7 they ordered as they were dispatched to Tickford for conversion, and the customer then received their fully converted Racing Puma, often this means that the date of first registration can often be up to a year after the original build date.

"When the car is in fine fettle the cost of running is pretty good, the Zetec engine has always been pretty efficient, easily delivering an average of over 30mpg. Although throw it around a track, where it belongs, and frequent revving 7,000rpm will see this halve rapidly.”

Simon says servicing should, in theory, be affordable. But you’re better off going to a specialist who knows Racing Pumas rather than a regular dealer. Given the small numbers these cars were made in, chances are they won’t have seen one in a while. This is especially true of cambelt replacement, which requires a bespoke tool that Ford dealers may not have any more.

Budget on a £250 service every 6,000 miles, while the cambelt needs replacing every five years or 80,000 miles, at a cost of around £400.

“All the Ford Racing Puma-specific parts hold the notorious 909 (or 908) Ford Motorsport part numbers,” adds Simon. “That means they come with what is commonly known as ‘FRP tax’!”

Except, that is, for tyres. Expect them to last 10,000 miles and cost as little as £70 a corner to replace.

Advertisement - Page continues below

Time to get the biggie out the way: Pumas rust. Next time a standard car passes you, eye up its rear arches. If they aren’t bubbling away at the surface you’ll be lucky.

The Racing is afflicted differently, however. Its burlier body kit is essentially stuck on over a standard Puma, so those rear arch extensions are actually welded and glued over existing panels. Hidden corrosion occurs between the two, and Simon estimates it affects 85 per cent of cars. “Unfortunately the only way to see this is to take the rear quarter interior trim and speaker bins out and look down the hole.”

Get it fixed with third-party bits via a friendly welder and you can spend £750 per side fixing it; get proper parts and that’s more like £2,500. So yes, you could spend £5,000 fixing both if you’re fastidious about these things. Ouch.

Up front, the wings can also suffer corrosion, but it’s usually a repair rather than a replacement job. Good thing, as the parts are very rare and will set you back up to £500 per side.

Front and rear bumpers are even rarer; made of fibreglass, their big issue is looking fractured if they’ve taken a bit of a knock. Simon says just five original rear bumpers remain – £600 a pop – while a genuine front bumper will be £1,000. But third party manufacturers produce much cheaper reproduction parts.

Have a poke around the boot, too. Make sure it’s not damp – it can take in water, which can lead to rot – while the floor can suffer a bit of rust too.

The suspension was a collaboration between Eibach, Sachs and Ford. “Unfortunately, the original springs and shock are no longer available,” says Simon. “So unless you can pick up a spare set from an owner then the only solution is to go to coilovers which does change the handling. Apart from that the rest of the suspension is either standard, or modified standard Ford parts bin stuff.”

The Alcon front brakes, though, are the expensive part of the car, and need plenty of maintenance. “Servicing, if used in daily conditions, should occur every 3,000 miles or so, to keep them tip top,” says Simon. “A lot of owners have two sets to allow them to switch over and get the others refurbished while not in use.”

“A badly maintained set of calipers could set you back over £700 to service if they require welding and machining,” he continues. “An amalgamation of water and salt causes them to rot badly in some case, and as with most FRP spares, new ones are no longer available. Standard front discs are no longer available but bell and rotor alternatives are around £400 a pair.”

Happily, the rear brakes are much simpler, with the discs and calipers shared with a contemporary Focus. They should be a doddle to maintain.

Inside, check for wear and bobbling on the Sparco seats and the lovely Alcantara-trimmed steering wheel.

If the seats are in a bad way, then a replacement pair will start at £500 for some that are a bit tatty, Simon saying there’d be a bidding war if a mint set turned up for sale, and £1,000 being the likely cost. Yikes.

Retrimming the wheel, meanwhile, will cost £250 plus the cost of the Alcantara required (it’s £200 per metre if you want the correct blue).

“If anything else needs replacement, the rest of the trim is stock Puma,” says Simon. “So most can be raided from scrap yards, but beware Puma interiors came in more than one colour: find an early car, pre-2000, with a Blue Alchemy interior.”

The engine is very strong, and there are several examples that have happily topped 150,000 miles. In fact, Simon says to be wary of low mileage cars, as it’s not an engine that likes to sit doing nothing.

It’s essentially a standard Puma 1.7 engine with a remap and higher lift cams, so if bad luck struck and you needed a new engine, sourcing a standard Puma 1.7 then carrying out around £150 of work would see you back to normal.

The gearbox also rarely fails, and again is a standard Puma item, just with its first two gears shortened. As mentioned earlier, it’s brilliant to use, so you’d have to be wary if the shift action didn’t feel supremely satisfying on a test drive.

“Around 80 cars were fitted with a limited-slip differential,” says Simon, “so this does make the car a little more desirable.”

How much to pay

So small was the Racing Puma’s production run, buying one probably won’t be a quick process. Especially if you want to shop around to buy something that’s properly tidy.

Prices start at around £6,000 for cars that are a bit tatty, with Racing Pumas in average condition costing £7,000 to £8,000. Something absolutely mint will, according to Simon, cost up to £15,000.

“My advice to anyone would be to buy the best you possibly can, as it will save you huge amounts of money,” he says. “A full restoration with proper bits will cost you over £10k, and whilst prices are appreciating fairly quickly, it will be a little time before you make your money back.”

Simon does say, though, that you shouldn’t necessarily steer clear of a Cat C or D damaged car, so long as it’s been properly repaired. “A recent concours winner was a badly damaged car, front and back, and had to undergo extensive repairs, but is now better than they came out the factory.”

“Why I love mine”

Kate Umfreville enjoys her Puma on road and track.

“It is hard to pin point the exact moment I first laid eyes on the Ford Racing Puma and the dreaming began, but I owned a standard Puma, and on a club trip in May 2000 I got my first ride in one. The whole experience was just fully involving from the noise and the hugging Sparco seats to the acceleration. I knew I needed to upgrade to a Racing.

“Ford started hitting the used market with ex-management cars, and a garage in the Midlands had some in; one had gone quickly and I didn’t want to miss out, so I placed a deposit over the phone without even seeing it.

“The following weekend I drove up and there she was looking stunning with only 4,666 miles. The deal was done, and a week later saw me driving back with my very own Racing Puma in February 2002. I was later to discover that my boot had been signed ‘last car off line’ dated ‘20/12/2000’ by a Tickford trim fitter. That made my day.”

“Every weekend saw me outside, washing my stunning car, thinking about what I was going to do and where I was going to go. I entered it into hill climbs and sprints, but while the Racing Puma was exhilarating, the granite walls surrounding the ‘Les Val des Terres’ course meant I couldn’t push past the subconscious concern of damaging my car. Trackdays provided the answer.”

“The thrill of track driving prompted the few modifications that I have done to mine. I have the LSD gearbox, a lower strut brace, Schroth Autocontrol harnesses, cosmetic changes and RPJ dampers. These Richard Parry-Jones dampers make the already firm Racing Puma that bit tauter, and it really sits there tight and flat on track. I have taken a drive through Europe to the Nürburgring in 2007 and oh did I love that, a real challenge.

“My car was a daily driver for a while, but more recently, my priority has been on preserving my Racing Puma by extensive body protection both inside and out against corrosion, as this is a keeper. This has been hard work and I have had help from a local mechanic for the work I couldn’t do, but it’s been an important project, a labour of love, and it is not finished yet. I’ve always had my car regularly serviced, maintained items proactively, and have drawn on the Racing Puma community where specific knowledge was needed.

“To this day I am still active with the Ford Racing Puma Owners club and Pumapeople and have many friends made through our shared enthusiasm for the car. I enjoy my Racing Puma as much today as the day I picked it up. I still grin and think, 'that's my car!’”

Trending this week

- Car Review

BMW 1 Series

- Top Gear's Top 9

Nine dreadful bits of 'homeware' made by carmakers