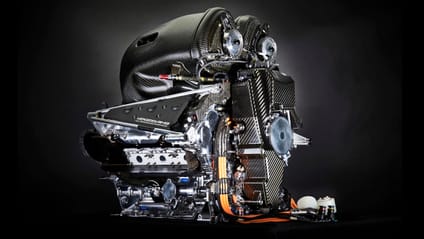

The secrets behind Merc’s unbeatable F1 engine

TG enters Mercedes AMG HQ and meets the man behind F1’s best car

Mercedes has run away from the rest of the Formula 1 grid in recent times. Click through for an insight into the engine behind all those wins - and Lewis Hamilton’s consecutive titles - from Andy Cowell.

He's the Managing Director of Mercedes AMG High Performance Powertrains, and he's keen on revolutionising the C-Class, entering Formula E, and even smaller engines...

Advertisement - Page continues below

TG: F1 engines are smaller than ever. Does that mean they’re more relevant?

AC: If we go back to 1989, we were running V12s and the European Car of the Year is a four-cylinder Fiat Tipo. But now we’ve got a set of regulations that aim to be road relevant, and powertrain engineers are driven to focus on lowering CO2. So following the road car direction, we have a 1.6-litre turbocharged engine, which arrived in the same year the Peugeot 308 - with a similar setup - was European Car of the Year.

In the road car world, none of us will accept a new car that has got less propulsion, a car that accelerates slower away from the lights. But all of us want a car that takes less time to fill up at the petrol station, because the longer it takes to fill up, the more it costs you. So F1 and road car missions are aligned.

So does that mean you’re all about fuel economy?

We’ve all used ‘mpg’ for decades, but here we focus on the thermal efficiency. That’s how much energy in the fuel we can turn into useful work coming out the back of the crankshaft.

If we use that as a measurement all the way back to 1879, 17 per cent was the number, which was revolutionary. Over the next 137 years we’ve crept along and ended up at 29 per cent, that’s where we were in 2013 with the naturally aspirated F1 engine, and it’s where most road car engines strive to get to.

The journey we’ve taken since 2014 [when turbos came back to Formula 1] means we’ve now got an engine with thermal efficiency of over 50 per cent. If you ignore the energy store [part of the hybrid technology], take that out of the equation, we’d have over 1,600bhp coming out of the crankshaft. [The engine’s real output is somewhere above 900bhp].

Advertisement - Page continues below

Are you happy F1 engines have downsized to V6s?

Perhaps six cylinders is too many, but in the world of Formula 1, a vee-shape works beautifully with the structure of the car. A V4: maybe that would have give us an improvement in efficiency. But a V6? Not bad.

But I guess these things evolve gradually. When you’re running a V8, going to a V6 feels like the first step, and a V4 would be the next step. Maybe in the future we make the engine a little bit smaller and we put an electric front axle on.

Why just one turbo, when performance road cars typically use two?

With twin turbos, it’s set up so that the smallest turbo spins up first to get some boost up, then the next one spins up… With the electric machine on this turbo, we can just spin the whole thing up as the driver goes through the corner, while he’s off throttle.

How much of this engine’s tech would you apply to a road car, say the C-Class?

Have I got complete freedom?! You would take the electric turbo. You would take the MGUK [the KERS], built into the engine. You would definitely go for a very small-capacity engine. Less than a litre. Maybe a v-twin. It would be the next step [from three-cylinder turbo engines]. 400cc, that’s a good number. Lets talk in cubic capacity, not litres.

It would have 200 horsepower. You would definitely have an electric machine to drive the compressor. There’s probably electric machines at the front corners to absorb braking, and it stays rear-wheel drive. How much is the engine doing? Is it not that the C-Class now has a 400cc, v-twin range-extender that sits there and operates at full throttle to feed electric motors?

Wow. Big changes. Do you see a future for internal combustion engines which aren’t hybrids?

No. I think there’s a beautiful partnership between high voltage hybrid systems and internal combustion engines, where they can help each other. There’s a huge problem with the mass of batteries in pure electric vehicles. Cars want to be low, aero, lightweight. As soon as you say ‘lightweight’ and ‘electric’ it gets complex.

You want a system that recovers kinetic energy, and a system that runs on gasoline, which has great energy density. But you want an engine that converts that at greater than 50 per cent thermal efficiency. Whether that’s propelling the car directly, or whether that’s helping you top the battery up, is the thing.

We just need to make sure electricity comes from an honourable source. What comes out from our three-pin socket hasn’t necessarily come from a great source.

Speaking of electricity: are you interested in joining Formula E?

Yeah, if we could do a bespoke energy store, electronic motor… When the sport frees up in terms of technology over the next few years, it becomes a more interesting proposition.

Are Lewis and Nico interested in your engine developments?

Yes. First and foremost they just want lots of power! They want to get down the straight quicker than the others, but the precision of torque delivery to the rear axle is what they really care about.

We talk about drivability: it’s down to the driver asking for a little bit more power, and getting it straight away. And when he asks for it another lap, he gets exactly the same. The last thing he needs is when he’s balancing the car on the edge and you suddenly give him too much and he’s off the circuit.

Our torque delivery with this turbo V6 engine is more precise than with the naturally aspirated V8, and that’s because of direct injection instead of port fuel injection.

Advertisement - Page continues below

Do they need much training when a new engine comes along?

When the new V6 came along in 2014, there was lots of driver in simulator work because the power curve is stronger and broader, and harder to manage. We went to Jerez testing; there’s a left-hander coming onto the straight, and we were watching the cars with the tail flick out at every gearchange. We saw a bit of that in Mexico last year, too. The altitude meant they lost a lot of downforce, because of the air density being thinner.

Lose the grip and you’ll get exciting cars! The more of the time the driver is the differentiator [between cars’ performance], the more exciting the race will be. If we increase full throttle times it’s just slot car racing, isn’t it? We ought to quantify that for each circuit - how much of it is down to driver balance. Too many engineers working on it, eh!