What goes on behind the scenes at a Formula One race?

TG sneaks backstage at the Singapore GP to find out how it all works

Entire cities have risen and flourished with less effort than the breadth of enterprise required for the construction, hosting and running of a modern Formula One race.

To paraphrase the 2015 Singapore GP victor Sebastian Vettel, running a grand prix is a fine lesson in ‘making the impossible possible’.

Words: Vijay Pattni/Pictures: Rolex/Jad Sherif

Especially considering the temperature in Singapore fluctuates between sauna and, um, Mordor. It’s really bloody hot.

Take a cool drink, then, as we cordially welcome you backstage at the world’s most glamorous race series, at a circuit that is fast becoming a fan and driver favourite.

Singapore is as precise as Monaco, but the consequences are higher when things go wrong

Rolex, official timepiece and global partner of Formula One, sneaked TopGear.com in through the back doors of the Marina Bay circuit in Singapore so we could see exactly what it takes to organise an F1 race.

Before we step backstage, though, a quick reminder of the significance of Singapore on the calendar, and why it’s generally one of the best to watch.

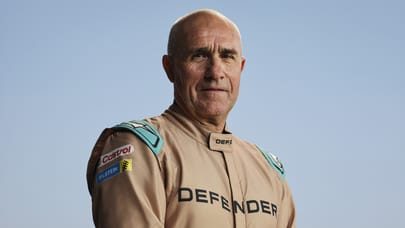

“It was the first of the night races,” says Tom Kristensen, himself a nine-time Le Mans champ. “It brings back a lot of things that race fans and drivers are passionate about. It’s a street circuit and it’s fast. Ninety per cent of the corners are blind, and you come in really close to the barriers.

“That’s part of the excitement. You really have to be ultra precise. It’s as precise as Monaco, but the consequences are much higher when things go wrong.”

The press room

Matteo Bonciani, the head of Formula One’s communications, agrees. “It’s very appreciated because it’s a street circuit, but you can have a little bit of glamour. Suzuka isn’t exactly the same thing,” he laughs.

Bonciani is the gentleman you regularly see on your telly screens, shuttling the drivers around, including to and from the press room. He explains a little bit about the logistics of putting up the race.

Top Gear

Newsletter

Thank you for subscribing to our newsletter. Look out for your regular round-up of news, reviews and offers in your inbox.

Get all the latest news, reviews and exclusives, direct to your inbox.

“For us, Formula One means we arrive at the circuit on the Monday or Tuesday, and we stay the whole week until Sunday or the following Monday,” he says. “We divide it up between five or six people, and each of us is a delegate, and every delegate has the responsibility for certain areas. I am the media delegate.”

Other delegates include technical – that’s Jo Bauer, responsible for scrutineering – and the medical delegate, there are stewards (four at every race, including a former racing driver), the safety car driver, and of course, race director Charlie Whiting, F1’s ‘friendly policeman’.

Once on the scene, the FIA team decamps and assesses the local situation. This year, Singapore had thick smog covering its skyline a few days ahead of the race because of fires in Indonesia.

“We had this haze,” Bonciani explains, “which means we have no visibility. And if we have no visibility, it’s a problem because the helicopter cannot fly. The helicopter has to fly because in case of an accident, the hospital has to be reached according to a certain procedure. Things like that are crucial to us,” he explains.

And visibility, in its wider sense, is what F1 is really all about in the modern era. The communications centre is a building unpacked and constructed for every race, housing up to 200 people working tirelessly on data, images and audio. It’s basically responsible for everything you see and hear on your screen.

The comms centre

We can’t show you pictures of the inside, sadly – it’s too top secret for that – but the FIA’s chief technical officer, John Morrison, takes us on a behind-the-scenes tour and explains the complexity of the broadcast operation. Incidentally, John looks like he used to be in a rock band in the 1960s, which definitely helps Top Gear’s understanding.

Let’s start with data. The comms building houses a mixture of engineers, technicians and production staff; the majority of which work on the TV programme. There’s super-fast fibre wire running all the way around the circuit, transmitting data back to comms.

“We put loops in the circuit every 200 metres, connected to trackside units,” says John. “There are around 30 units in Singapore, and the cars all carry transponders. When they cross the loop, they fire data down into the loop, and the loop sends a little message back to them.

“The events produced by that are used to produce the overall timing of the event. Sector times, lap times, the position of the cars, everything. We can tell the car when it’s in a DRS zone for instance, and when it can use it,” he adds.

Another software engine then calculates the timing pages, which are then beamed to everybody at the circuit. “All the teams use this, the FIA uses it, journalists, commentators… everybody in the circuit. We send the teams this in data form, and they inject it into their analysis engines so they can make the necessary adjustments.”

Moreover, this software – a bespoke system devised internally – can even adapt to, say, the introduction of a red flag. “It will readjust the position of the cars based on the rules of the event,” says John.

A small team crunches through data, while another uses the data to produce the on-screen graphics: revs, g-force, speed and so forth. Yet another team edits together video packages for additional broadcast content (the ‘red button’ type stuff you generally see), and there are people working the on-board cameras (each car has a front- and rear-facing camera).

There’s even a team adjusting the colours of the cameras dotted around the track, to make sure the levels match, one team superimposing virtual, digital adverts in hard-to-reach areas of the circuit, and a team listening to all the radio messages between the driver and the team.

The final programme goes out to half a billion people worldwide

“There are 26 cameras around this circuit,” says John. These feed images into a bank of 26 monitors in the main heart of the production area – a sort of Batcave – where the executive director dictates what we all see. “There are guys talking to the track cameramen because the director has told them we’re – for instance – following Vettel, telling them what kind of shot we need. The director may go to the onboard, he’s got to put in replays, there’ll be suggestions for radio messages, the graphics guys will work up graphics onto the image.

“He’s taking all of this and mixing the final programme that goes out to half a billion people around the world,” John says.

Race Control

The heart of any Formula One race, and a room of silence, thick with responsibility and many, many screens, covering practically every millimetre of the circuit.

Race director Charlie Whiting is the man in charge of keeping the race run safely and to FIA regulations, with his deputy race director Herbie Blash sat alongside him on the front row of the room.

Not only are Charlie and his team – comprised of the regular FIA delegates and representatives pinched from local clubs – able to see everything, they’re also privy to all the data fed from the broadcast centre, and are in immediate contact with marshals’ posts, the safety and medical cars, and the stewards.

“They listen to everything, see everything, and everything is recorded,” explains Kristensen.

Scrutineering

The kingdom of Jo Bauer – the F1 technical delegate – is run by a team of scrutineers whose job it is to make sure the cars comply with the rules set out by the FIA. There’s a giant weigh-bridge used for the cars, which have to be at least 691kg including the driver and fuel at all times during the event.

“Initial scrutineering starts on a Thursday,” Jo tells us, “checking safety items on the cars. Things like the ERS light, wheel tethers – which are the ropes inside the suspension members – the seatbelts… everything.”

There are a group of 30 scrutineers sourced locally working for Jo, who briefs them extensively. There are two in every garage. “We can’t do it on our own,” Jo says, “it’s just too complex. Every delegate has his own team and we have to rely on them.”

The safety car

Move outside of scrutineering and you’ll find a smiling Bernd Maylander perched alongside the brand new, 502bhp Mercedes-AMG GT S safety car. “I have two of these because we’re also supporting the support races, and it’s always good to have a backup,” he says.

The baby AMG takes over from the gullwinged SLS, don’t forget, as Formula One’s official safety car; the car responsible for pulling together and slowing down the cars on track, and leading them in procession until the track is safe again to race.

Bernd – who’s been the safety car driver for 17 years now – is happy with his new ride. “The SLS was a fantastic car but this is the new generation,” he tells TG. “It’s quicker than the old SLS around these tracks, I think, and also really good fun, too.” We know, Bernd.

The routine is this: on the Thursday before the race, Bernd and his co-driver will head out onto the track and go guns blazing in the GT S, figuring out the limits of the car, where it starts to slide, riding the kerbs and everything.

“We’re really pushing the limits,” he says. This is because when it comes to race day, he’s got all the knowledge of how the GT S behaves, and make sure he can lap at sufficient pace to keep the F1 cars from overheating. “The race has to be safe.”

He’s sat in the safety car the entire time during the race, and both Maylander and his co-driver are in direct contact with Charlie Whiting. “We get all the commands from Charlie and Herbie. We report to race control on what we see on the track,” he says.

A neat reminder of just how hi-tech and closely scrutinised modern F1 has become comes from Sir Jackie Stewart, another of Rolex’s ambassadors and a three-time Formula One champion.

“In my day, if I’d made a little error of judgment or something on track,” he tells TG, “by the time I got back to the pits I could have dreamt up a wonderful excuse.

“Nowadays, these guys would know exactly what I’ve done before I know it..."

Trending this week

- Car Review

BMW 1 Series