Sweet sixteen: the story of the BRM V16 and its comeback

Somewhere in Lincolnshire, the world's most outrageous F1 engine is being brought back from the dead

The terrible temptation of the ageing Formula One fan is to opine that motor racing isn’t as exciting as it used to be. This is rubbish. But one thing that is categorically true is that contemporary F1 cars don’t sound as good as their predecessors. Today’s hybrid engines are weedy compared with the normally aspirated V8s that they replaced, which in turn weren’t as sonorous as a Nineties V10 pulling 17,500rpm, never mind the V12s that came before them, yada yada yada...

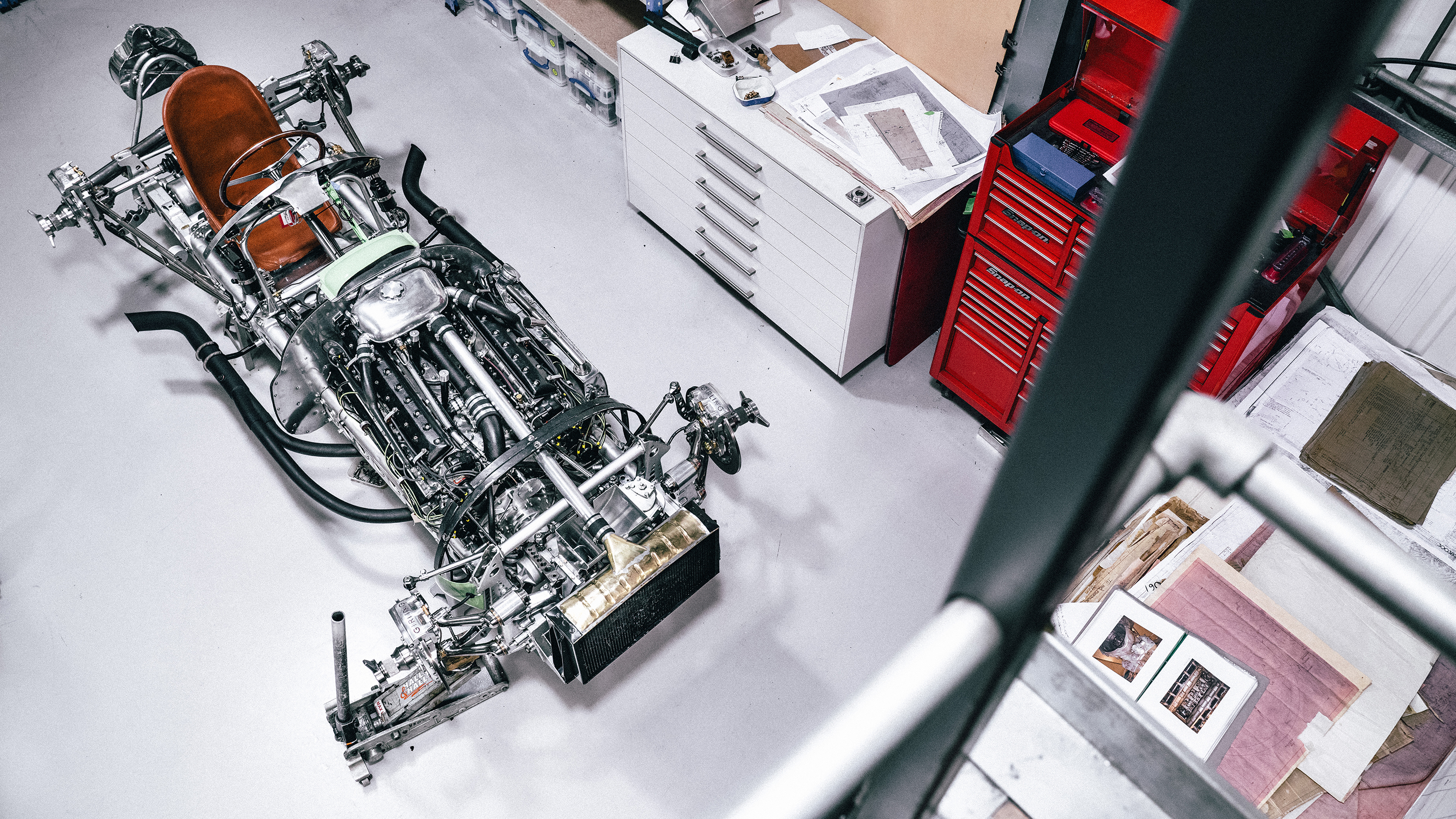

Yet all must kneel before the mighty BRM Type 15 V16, a post-war monster consisting of 36,000 separate parts that makes a sound like gathering thunder on a day when said thunder is dealing with a particularly nasty hangover and has just stubbed a toe on the door frame. It’s well worth a Google, except that no computer speaker can handle the vast complexity of the sound this thing makes.

Photography: Huckleberry Mountain

In fact, everything about the first BRM is complex. Even Einstein would have had trouble figuring out the physics of this engine. Here’s the key fact: largely indebted to the British aviation industry, and despite having 16 cylinders, the inaugural BRM engine displaced just 1,490cc and produced 600bhp at almost 12,000rpm. This was in 1950. It would be another 30-plus years before an F1 engine would match that.

On which basis, you may wonder why the BRM hasn’t been awarded a particularly grand seat in the pantheon of the greats. In a word, reliability. The V16 may have been technically mesmerising, but it was also fearsomely complicated. As indeed is the story of how it came about in the first place.

“Did the engine actually get to 600bhp? Did Fangio reach 200mph in it?” Simon Owen, grandson of BRM’s main man Sir Alfred Owen, ponders. “We don’t think that the BRM story has been told properly. The company started in 1947, the same year as Ferrari, and in our Sixties pomp in Formula One it was often BRM versus Ferrari. Obviously Ferrari carried on, we didn’t and it all petered out in the mid-Seventies. But we want to throw some light back onto BRM and what it achieved because it really is an incredible tale. And it begins with the Type 15 V16.”

Even Einstein would have had trouble figuring out the physics of this engine

The ‘we’ is Simon and his brother Nick, acting on behalf of their father John, along with cousin Paul. They’re all scions of the Rubery Owen dynasty, at one point the biggest privately owned company in Europe, employer of 17,000 people, and the prime mover behind this quintessentially British motor racing odyssey. Simon talks animatedly about the BRM archive, a vast trove of blueprints, archive material and memorabilia that amounts to a sociocultural history of Britain during this fascinating post-war period as much as it does a brand history.

But for now the main focus is on building the three ‘new’ V16s that were originally planned and had chassis numbers allocated alongside the three that did make it. His father John, who was at BRM’s original test base at the Folkingham airfield in Lincolnshire when Juan Manuel Fangio tested the car, will be getting one. “Watching the likes of the Pampas Bull [José Froilán González] and Fangio master the power of the V16 was very special,” he recalls. “In a selfish way, I have always dreamed of hearing that sound again but now I’d like to share the sensation with others.” The other two are up for grabs, a rare prize indeed among the well-heeled and knowledgeable historic racing fraternity. The job of reincarnating them has fallen to globally renowned historic motorsport specialist and BRM experts, Hall & Hall.

Before we get into that, we need to delve into BRM’s history. That takes us to the doorstep of a certain Raymond Mays, who dispatched a letter to the leading figures of British industry a month or two before World War Two actually came to an end pitching the idea of a national Grand Prix racing team. Mays is one of those characters you simply couldn’t make up: he attended the prestigious Oundle School where he knew Amherst Villiers – who would later develop the supercharger used on the Blower Bentleys and would become immortalised in his friend Ian Fleming’s first James Bond novel – and was a successful driver in the early days of motor racing.

There’s a fabulous photograph of him driving a Bugatti in a hillclimb in Caerphilly, staring aghast as a rear wheel shears off and overtakes him. In 1933, he co-founded English Racing Automobiles, but he built out on this idea when he used his connections and charisma to sell the idea of a British racing team to rival the predominantly French and German giants of the time. Patriotic industrialists such as Oliver Lucas, Tony Vandervell, David Brown and Alfred Owen were the leading lights in a consortium that encompassed more than 100 companies, variously promising financial or material support. Game on.

Alongside former ERA mainstay Peter Berthon, British Racing Motors was founded in 1947, based in the Old Maltings behind Mays’ family home Eastgate House. The first BRM was conceived as a showcase for British engineering genius and know-how. Thus the car acquired its astonishing technical specification, its power unit directly inspired by the Merlin engine that had proven so key to the success of that glorious warbird, the Spitfire. Prime among its features was the Rolls-Royce centrifugal two stage supercharger, a device that required 124 separate components supplied to BRM by 24 external suppliers. It had a vee angle of 135° and every nut, bolt, bracket and steering arm was exquisitely manufactured from solid pieces of the highest quality steel.

“The supercharger has two oil filters, two scavenge pumps, two pressure pumps and crossover gears,” Rick Hall tells me. “Some of the machining in there has proven difficult with modern techniques. Yet back then the guys were working with lathes and mills, there were belts and all sorts flying around.

Top Gear

Newsletter

Thank you for subscribing to our newsletter. Look out for your regular round-up of news, reviews and offers in your inbox.

Get all the latest news, reviews and exclusives, direct to your inbox.

“You look at the engine and can’t believe it’s only 1,500cc with a whacking great supercharger on it that can run at four times the engine speed. In fact, I knew the guy who designed it. I’ve got a Merlin engine downstairs, you can see that this is basically a scaled down copy of it. A lot of the parts on the V16 are like jewellery, they’re just beautifully made.”

Says Hall: “The rev counter drive alone must have 50 pieces in it. Of course, they could have had a housing with a cable on it, and it would have been job done. But they insisted on using what the aero industry had done. In those days it didn’t matter how difficult it was – the attitude was, we’re going to do it.”

Fair enough. Except that this bloody mindedness led to delays, and when the car did run it would spin its wheels in fifth gear at 140mph...

The pressure to deliver soon became intense. The engine would repeatedly misfire at 11,000rpm during testing, and there were problems with the way the cylinder liner was sealed up into the head. This led to countless explosive failures. With the countdown on to a scheduled gala appearance at the BRDC International Trophy at Silverstone in August 1950, Berthon was now living in the control tower at Folkingham airfield. This wasn’t just about debuting a new racing car, it was a matter of national prestige. In the event, Raymond Sommer managed three laps to qualify for the race, Mays one, but both BRMs swiftly expired on the grid. It was an embarrassment, of course, not least because the outside world had no idea what divine madness was occurring within that engine. A lunched engine is a lunched engine.

A young Stirling Moss would later grapple with the supercharger’s relentless boost while testing the car at Monza, and it’s thought that the power output rose from 160bhp at 7,000rpm to 380bhp at 9,000, and on to more than 600bhp beyond 10,000rpm. Imagine trying to race the thing.

The situation would improve, though. In 1953, BRM raced 11 times, and even won a few races. Fangio and González appeared to have conquered the unruly beast. It had a successful afterlife in Formula Libre. A lighter, friendlier MkII was commissioned, with Tony Rudd – later to achieve greatness as the father of ground effect at Lotus – dispatched by Rolls-Royce to oversee things. In September 1952, Rubery Owen assumed control, and the grand adventure could really begin. In 1962, Graham Hill won the drivers’ championship and the team the constructors’ title. Among the driving alumni you’ll find names like Mike Hawthorn, Jackie Stewart, Dan Gurney, Pedro Rodríguez, Jo Siffert and Niki Lauda.

But if history records the V16 as a folly, it’s surely one of the greatest in motor racing history. “There are a lot of things that can go wrong. We’re not reinventing the wheel because they did that,” Rick Hall notes. “But it’s the same complex piece of machinery we’re talking about. Until you see the amount of design and effort that went into it, you really can’t fully appreciate it. It was intended to be the most powerful Grand Prix car ever. To make something so complex reliable at the sort of revs it was doing was years ahead of what anyone would have imagined at the time.”

Trending this week

- Car Review

Honda Prelude