Happy birthday, Stelvio: celebrating a 200-year-old mountain pass in a Lamborghini

What do you get the road that has everything?

“Today is the third greatest day of my life.” Hans-Joachim Stuck has tears welling in his eyes. “After the birth of my two sons, nothing I’ve done has matched this. Nothing.” This from a man who has stood on F1 podiums, won world championships in sports cars and DTM, been victorious at Le Mans twice.

Hans-Joachim Stuck has just driven up the Stelvio Pass. He was in an Auto Union Type C. An exact replica of the car his dad drove in the early 1930s on his way to earning the nickname Bergkönig (king of the mountains). Being gallant I could put junior’s tears down to the pungent rocket fuel the V16 runs on, but actually I think a little emotion is allowed here.

I’d got a lump in my throat watching it come up here, this little bright silver dot, audible as soon as it was visible, almost six miles and 820 vertical metres further down the pass. It was alone, nothing around it, while above hundreds of us stood excitedly on the mountainside, listening to the faint yet furious rock loosening thrash of its unsilenced V16 as it shook the geology.

Photography: Rowan Horncastle/archive

The 200th anniversary of the Stelvio Pass. That’s a good enough reason to bring an Auto Union out of retirement, right? It’s not alone. On a grey, blustery, chill day around 150 cars have set off at intervals from the historic start line outside the Bella Vista hotel at hairpin 46 to scale the original hillclimb course. Many, including a magnificent Mercedes-Benz SSK, have direct links to the history of this famous road.

A road built 200 years ago. The Habsburg empire (bet you didn’t expect to be reading about that on TopGear.com) had come off badly in its first skirmishes with Napoleon, and realised that in order to move troops quickly between its provinces if things got fighty again, it would need a proper road over the mountains. This whole area was part of the Austrian Empire back then, and the pass in the shadow of the mighty Ortler mountain that divided Tyrol (the more iconic northern flank) from Lombardy to the south was its only option. In 1818 Austrian emperor Francis I issued a decree for the construction of a military road.

The engineers were prepared. Ten years before that, early studies had envisioned a road 3.5 metres wide running at an angle of up to 15 per cent. But we have the cannon to thank for what was eventually built – a road at least five and a half metres wide, that rarely climbs at more than 10 per cent, with hairpins that follow carefully calculated radii. Gun carriages were heavy and hard to manouevre, horses could only cope with so much. These were the exact elements that prescribed the design of the road.

It doesn’t follow the original design laid out by architect Carlo Donegani either. That called for 61 hairpins rather than 48 on the steeper Tyrol side, with a ladder of 22 climbing the precipitous cliff at the head of the valley. The reason for that was to minimise the risk of avalanches closing a road that was intended to be passable year round (in 2025 it’s still closed for six months of the year) and equipped with covered galleries and shelters.

Top Gear

Newsletter

Thank you for subscribing to our newsletter. Look out for your regular round-up of news, reviews and offers in your inbox.

Get all the latest news, reviews and exclusives, direct to your inbox.

But when it came down to it they simply didn’t have enough rock and material to build the mighty 12 metre high buttresses that would have been required to construct that many tightly stacked hairpins. So a new route was found that sweeps out to trace the northern flank of the valley, with fewer hairpins and more exposure to avalanches. While the calculations for this were going on, thousands of men (and some women) were already toiling away on the Lombardy climb from Bormio, which was completed in 1822. It then took 1,500 labourers three more years to construct the cathedral-like buttresses that carry the road up the precipitous Tyrolean flank. Final cost? Exactly 419,658 Austro-Hungarian guldens. You try and do the conversion on that.

Take yourself back. Imagine the work that went on here. There were cobblers, inns, stables, tool makers, wagon drivers. There were rocks falling, picks swinging, people toiling year round in all conditions. We go and enjoy the road, the view, but I’d urge you to consider the history of these places – not just the Stelvio, but the Grossglockner, the Galibier, the Furka, any of them. Because as feats of engineering they are exceptional.

Back in 2008 we declared this the “greatest driving road on the planet”. As anyone who has been there can attest, it isn’t and never has been, so don’t come here for the thrills – other places do that better. Come here and marvel at the huge towering walls and fortress-like constructions that have stood firm against the forces of gravity, weather and environment for 200 years. There’s nothing quite like the Stelvio for the sheer drama of its setting, the boldness of its route. It’s the undisputed champion of mountain passes.

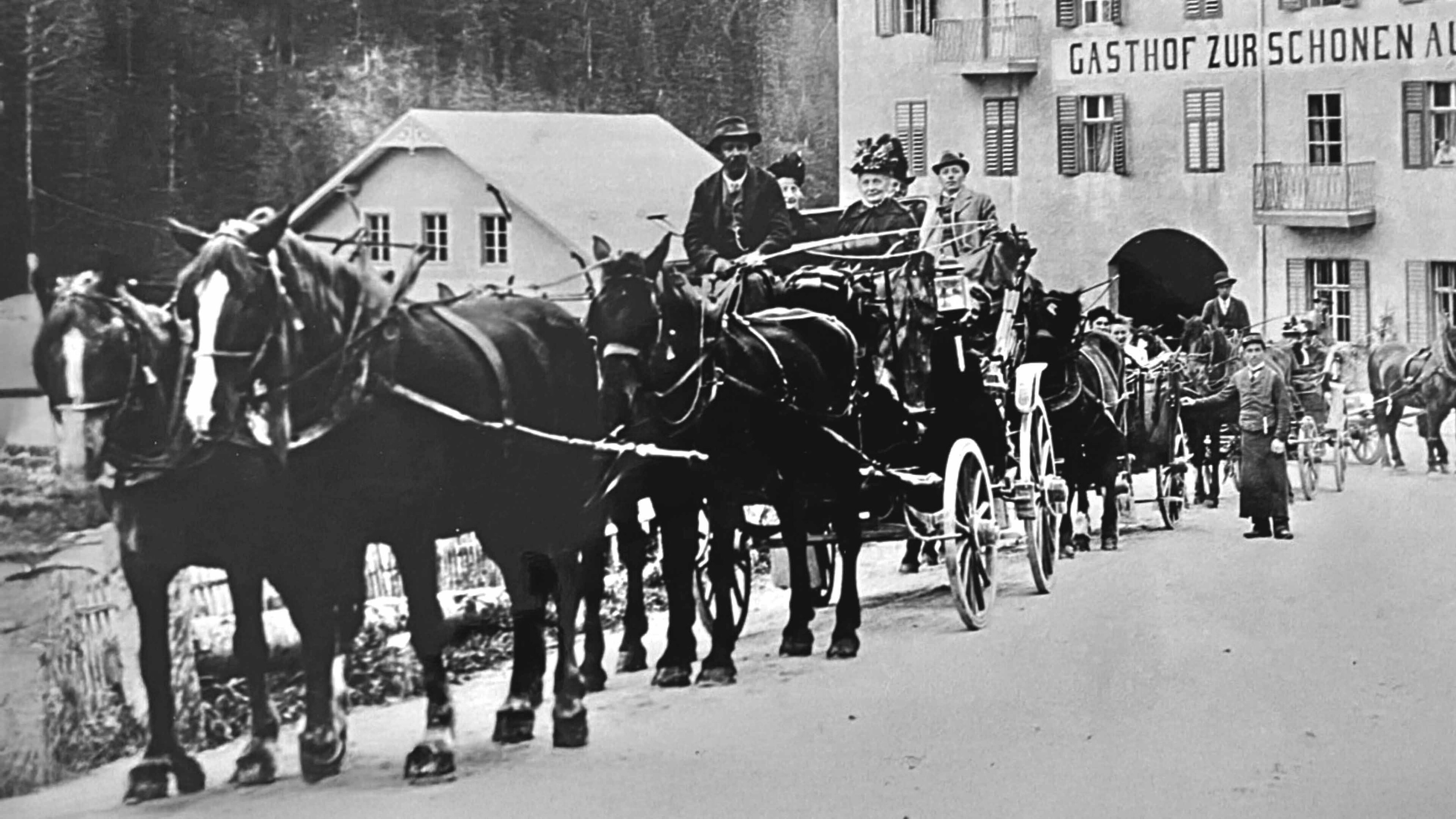

So of course it’s drawn people. Despite the ongoing sabre rattling of empires, the Stelvio was a tourist hotspot pretty much from the moment it opened, a coach trip over it was considered a key part of a Grand Tour. Huge hotels were built (the Grand in Trafoi had its own orchestra and photographic dark room) and soon the motor car got involved. Until 1936, the 2,757 metre Stelvio was the highest pass anywhere in the Alps, the greatest test of man and machine. It was first climbed by car in 1899. The following year a Hungarian count drove from Trafoi to Bormio and back in a day. Pass collectors started turning up – ascending it was a badge of honour.

There’s nothing quite like the Stelvio for the sheer drama of its setting, the boldness of its route

And soon after, the racing began. The heyday was the 1920s and 1930s, the surface still gravelled, but many corners were banked with concrete to boost grip and speed. When Stuck Sr won here in August 1932 in a Mercedes SSKL, the full ascent took him 15mins 23secs, with the Alfa Romeo of Tazio Nuvolari 20.6secs further back. Today I still think you’d be pushed to go much faster. World War Two rather got in the way, and in its wake the hillclimb scene faded, replaced largely by long distance Alpine rallies. The Stelvio remained a centrepiece, but as an individual challenge its time had passed.

Until today. The gathering at the start line includes everything from Amilcar and Alfa Romeo to DeLaHaye, Bugatti and Maserati. All have a grimy oiliness that speaks of frequent use. Adventurous types have piloted a pair of Frazer-Nashes from the UK, Audi has sent along a Wanderer Stromlinie W25 and the polizia have turned up in a pristine Italian Job Alfa Giulia Super complete with warbling siren. And a Huracán with over 200,000 miles on the clock.

Meanwhile I’ve turned up with an original 25th anniversary Countach and an iridescent Revuelto. The previous evening Rowan and I had driven them up the Stelvio at sunset in a reminder of what giddy heights this job can sometimes deliver. The Countach had been joyfully awful. Chief mechanic Vincenzo, who’s been working at Lamborghini for over 30 years, used the international sign language of driving to prewarn me. He pats my left leg and says “forza”, another “forza” while he steers an imaginary wheel, then leans in to wag his finger at the aircon, “no work”. Oh brilliant.

Strength and conditioning types bang on about plyometrics and calisthenics. A Countach costs about the same as a gym membership these days, so I’d have one of these. You get a far better soundtrack, too. The V12 is dirty, lumpy and raw, needs revs to clear itself out and even when it does, isn’t actually that fast. Couldn’t. Care. Less. Nor do I care that the turning circle is so horrendous that many hairpins require reverse. Or that the dash reflections make forward visibility a lottery. Or that the driving position is plain bizarre. Because if I’ve ever had a moment in my career that I would love to take eight year old me to, it would be those 20 minutes I spent ascending the Stelvio in the first car I ever loved.

I don’t care that the last of the line Countach (largely the work of one Horacio Pagani) was the ugliest, nor that it’s not actually that fast, I simply adore it. I love the physical exertion, coaxing the controls, that it does nothing to help you and everything to challenge you. Because on that long straight above hairpin 15, the first time I get to use third gear, the Countach feels sensational. What a way to travel, what a way to experience this place.

But the next day it’s the Revuelto that I line up alongside the police Huracán to take the lead in the parade. Alternator issues. I go off for a wander around the paddock and come back to find the Huracán’s driver giving my wife his phone number. Only in Italy. A few minutes later he saunters back over and asks if I’ll be OK to keep up with him. “You not take any risks, OK?” I can’t help but admire the bloke.

I want this experience to last as long as possible. This time I’m much less occupied by the car

In the end we don’t ascend in a flurry of wheelspin and wounded personal pride, but just extend the cars when the road allows. And that’s fine with me, because I want this experience to last as long as possible. This time I’m much less occupied by the car. The Revuelto has potent aircon, good steering lock, a tractable engine and a smooth gearbox. It’s light in my hands, responsive, I steer with my wrists not my shoulders. Progress over the Countach can be measured in light years, but they have this in common: both put the V12 on a pedestal and celebrate it. Long may that continue.

Top Gear has had a long relationship with the Stelvio. Jeremy, James and Richard finished here in their search for driving nirvana. Three years on from that we closed the road and shot Speed Week. That was memorable. The weather was shocking. I drove a Veyron Super Sport down the pass at night while a lightning storm lit the place up and rain bounced so hard off the road it was like driving through fog. Slowest, most tentative drive I’ve ever done. Back in 2022 I came before the road was opened for summer, just us and the marmots, bringing a Sián-based Countach. I’d have an original, thanks.

Every time we’ve been, we’ve done the same thing. If you come here, I’d urge you to do the same. Drive up to the Tibet hut for the best view down, stand there, ideally early in the morning when the sun rises down the far end, and just contemplate a view that, for us petrolheads, is one of the most astonishing on the planet.

A vast glaciated valley that wears its slender road like jewellery. That’s where I found Hans Stuck later. The Auto Union had been the last car up, treating the Stelvio to sights and sounds it hadn’t experienced in 90 years. “This has been amazing. Being in the car, with the goggles – they were misting up! It was so emotional for me. I don’t really think much has changed since my father raced here. I just think of the history that has passed under the wheels.”