Adrian Newey: "we really only have one master and that’s the stopwatch"

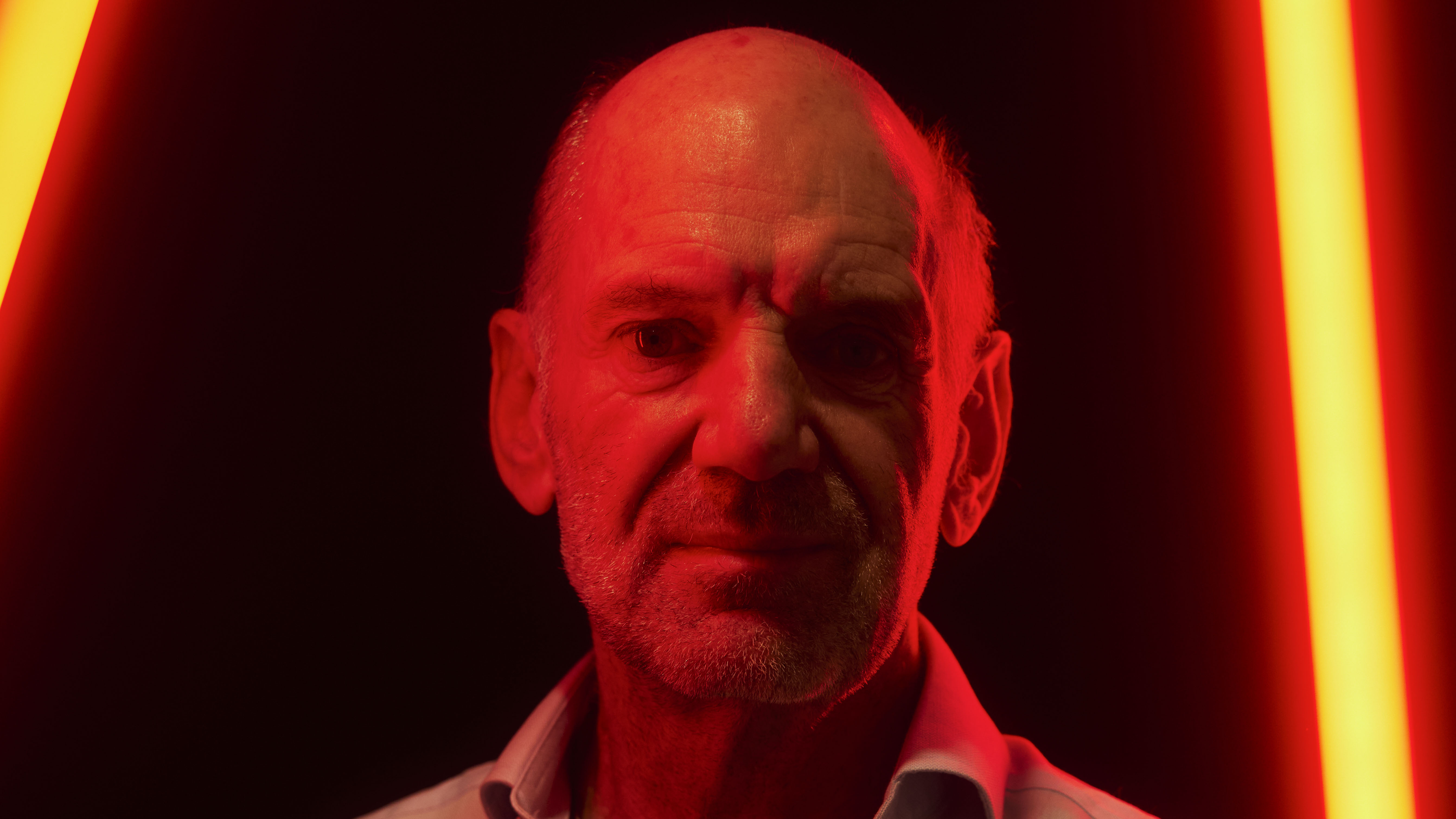

Newey won TopGear.com's 2023 Lifetime Achievement Award: here's how he looks back - and forward

Adrian Newey’s autobiography is called How to Build a Car. It’s a rather dry title that suggests there might be a certain aridity of tone within. It’s actually very funny in places, not to mention intriguing, inspiring, and an insight into the man that many regard as the greatest F1 designer ever – his cars have won 12 F1 Constructors’ Championships and enabled 13 Drivers’ Championships (last season alone, his car, the most dominant F1 car ever, garnered 21 wins from 22) and there was also conspicuous success in IndyCar in the Eighties.

So innate is his ability to understand the vagaries of physics and aerodynamics that any opportunity to talk to Newey – and it’s rarely granted – is underpinned by the naked terror of simply not being able to keep up. But he’s affable, engaging and smiles a lot. He’s just returned from Daytona where he was racing his GT40 with Ford CEO Jim Farley. I also discover he lived in the turbulent Compton neighbourhood in South Central LA during the mid-Eighties. The man who draws F1’s fastest cars by hand has clearly had quite the life. We thought it was time to celebrate it.

Top Gear: Congratulations on winning our 2023 Lifetime Achievement award. Do things like this matter to you?

Adrian Newey: I’ve been lucky enough to win a few things, outside the race wins. I prefer to look forward, but I do very much appreciate you guys recognising what I’ve been up to. It prompts a time of reflection.

TG: Did you always have a clear job goal?

AN: I knew what I wanted to be from the age of 10, and I geared my education around that. I was lucky enough when I graduated to go straight into working as an aerodynamicist for an F1 team – as a junior aerodynamicist and senior one because I was actually the only aerodynamicist.

I love the fact that I’ve managed to do what I always wanted to do and have had a great time doing it. The most difficult bit was actually getting the first job. I wrote to every F1 team I could find the address for and most didn’t reply. Landing the first job at Fittipaldi was partly down to preparation, perseverance and a bit of luck.

TG: It sounds like you were something of an outsider at school. Did that affect your path?

AN: I think it must have done. I never particularly enjoyed school. I went to a convent school until the age of six at which point I still couldn’t write because I was left-handed and the nuns had made me sit on that hand. I wasn’t very good at making friends, and I had to take a bus 10 miles to school which meant that the friends I did have weren’t local.

So I spent a lot of my holiday time alone making Tamiya scale models until I got bored making other people’s designs and started making my own, using bits of aluminium and fibreglass. My father was a veterinary surgeon but also a great car enthusiast. We had a lathe and basic metalworking machinery in the garage. I was actually picturing something in my mind’s eye, sketching it on a piece of paper, and turning it into an object.

TG: You studied aeronautics and astronautics but professed to have no real interest in the latter...

AN: Or the former [laughs]. My burning desire was to get into motor racing as a design engineer, and I figured that aircraft were closer to racecar technology than any other engineering discipline. So aeronautics was the logical choice and Southampton seemed to have the closest links to motor racing.

TG: An Adrian Newey spacecraft would be fun, though.

AN: Dangerous, I think. There is a requirement for them to come back in one piece. Actually, an American company did ring me up, about 10 years ago now, to ask if I would be interested in joining them to work on a spacecraft. It would be fascinating, and the space race in the Sixties must have been incredibly stimulating. But I find motor racing more fascinating. There’s a tremendous pace of development and involvement in motor racing. I like that.

TG: Does it surprise you that it’s still possible in this day and age to create a car as dominant as the RB19?

AN: It does actually. It’s a complete surprise. For the ’22 season we had the biggest regulation change on the chassis side since 1983, in terms of going back to venturi cars. We thought as we headed into the second year, with almost no regulation change over the winter and us running what is in effect an evolution car, that our advantage would be diminished, if not eradicated. Clearly that’s not how it’s panned out.

Top Gear

Newsletter

Thank you for subscribing to our newsletter. Look out for your regular round-up of news, reviews and offers in your inbox.

Get all the latest news, reviews and exclusives, direct to your inbox.

TG: You’ve won championships at three different teams. It’s intriguing that you’ve flourished within such different organisations.

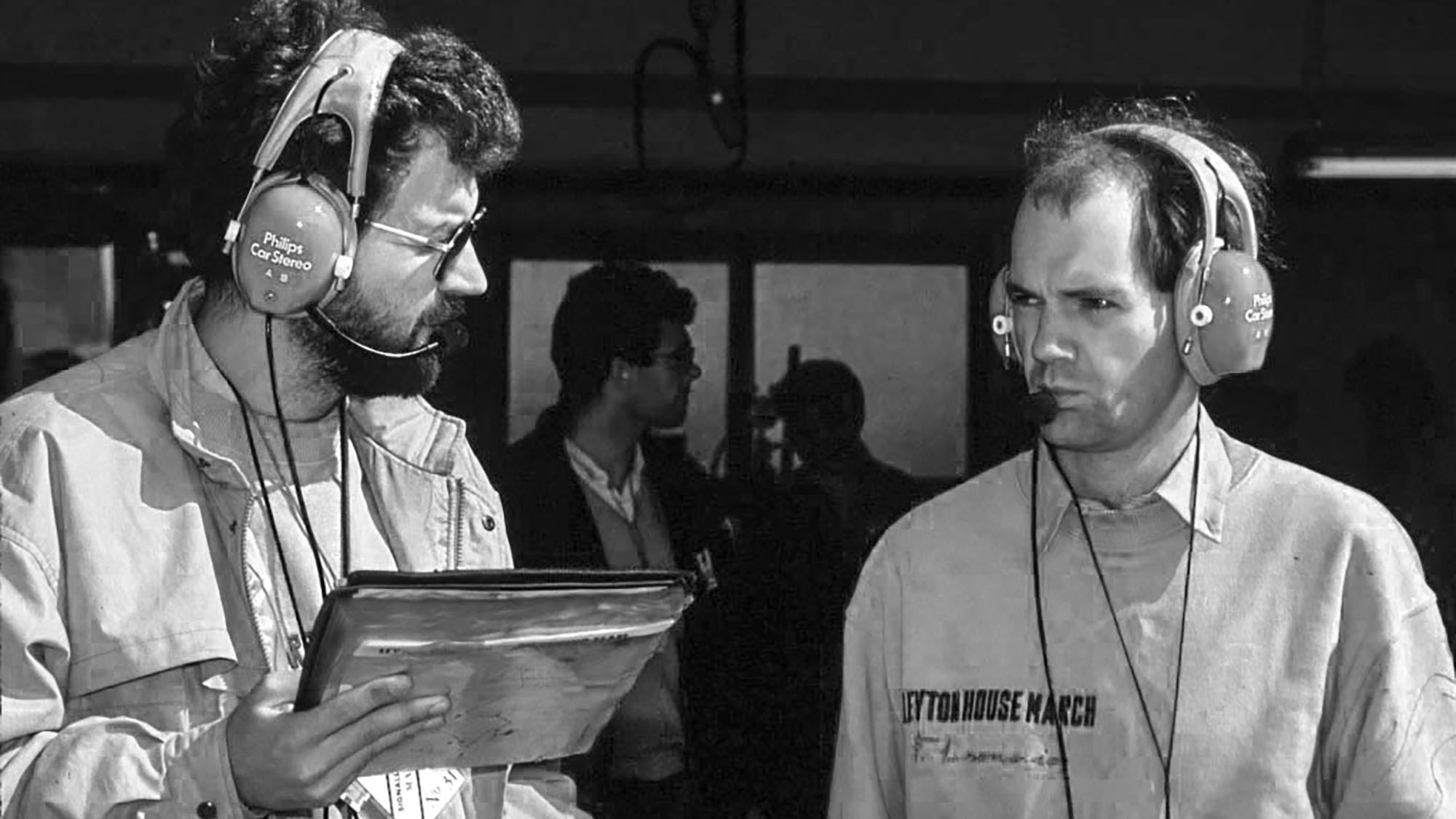

AN: Williams and McLaren were very different. I joined Williams from a tiny team, Leyton House. When I left there in 1990, there were still only five engineers and we were all self-taught. Williams was obviously an established team that had won championships long before I arrived. Patrick [Head] had created a very well oiled engineering structure, which was perfect for me because my passion was in making the car go faster. Williams had got a bit lost on the design side and hopefully I was able to contribute to correct that.

McLaren had a very different feel. Williams was effectively Frank and Patrick’s hobby shop, family run if you like, with the strengths and occasional frustrations that came with that. Whereas you had Ron [Dennis’s] huge attention to detail at McLaren, and it felt like a bigger company, like I would imagine British Aerospace to feel, although the engineering team was still pretty small by today’s standards.

TG: You also seem to be at your best when the regulations change.

AN: I’ve always enjoyed regulation changes. Not just because of the loopholes that may exist but figuring out the demands of the regulations, how they affect the fundamental principles of the car’s layout. For 2022, there were a few things that we needed to do differently. It was the return of ground effect – venturi – and I was certainly aware of the pitfalls having worked in IndyCar with that format [during the Eighties].

Bouncing is not simply due to the aerodynamic shape of the car, there are other factors – suspension characteristics, body stiffness – and when we were designing RB18 we were very mindful of that. We had a bit of porpoising at the very start but we were on top of it by race one.

TG: Why did no one else figure it out?

AN: Simulating bouncing in a wind tunnel and more so in CFD is not easy. It’s a transient problem, and there’s no motion to the car relative to the road. You don’t see it if you’re not looking for it. That’s the thing with all simulation tools. They’re dependent on what you put into them. If you haven’t looked in the right place and put the right things in, you won’t get the right answers out.

TG: And of course you draw by hand...

AN: The drawing board is a way for me to get the ideas out of my head and onto a medium I can develop them with, but you still need that spark. The subconscious is an amazing thing. I’ve had it many times when I’m stuck on something, give up and go and have a coffee or something. One day, one week, one month later, and a solution pops up.

TG: Can you tell immediately if an idea is worth pursuing?

AN: That comes from experience. It also taps into the managerial and developmental side of my job. Working with my colleagues is an aspect I really enjoy, and even if I feel an idea isn’t a good one it’s possible I could be wrong. I certainly don’t want to stifle anyone’s creativity, and it’s important to be encouraging. But we also have to be efficient, especially in the cost cap era.

TG: Do you still have genuine eureka moments?

AN: They’re rare but they do happen, and they’re very satisfying. You might think it’s the best idea ever, but you have to be very disciplined about proving it out. It’s a long process, but if it results in something that goes on the car and the car then goes faster that’s very satisfying. Once you take reliability out we really only have one master and that’s the stopwatch.

TG: Is AI going to affect F1?

AN: At some point it will, but it’s much more difficult to ascertain the timeline. AI is a broad buzzword term but it’s really an extension of ‘machine learning’ with a bit of internet thrown in, and that’s been around for ages. We’ve been using stress analysis optimisers for years [FEA or finite element analysis] but the human ultimately still seems to be better than the optimiser. It’s a tool but they absolutely do not replace the human.

TG: You’ve worked with some of the greatest drivers in motorsport. Is there one underlying characteristic that strikes you as most important?

AN: Selfishness, though that’s not to be confused with meanness. ‘Focused’ is probably a better word. If that means shutting out other things in life while you’re in the zone, then that’s what you have to do. The other key thing is having spare mental capacity. I’m not going to name any names but there are some drivers who can drive quickly for a period of time but you know that every available neuron is going into that process. There’s nothing left to think about how the race is unfolding, to adjust the car, manage the tyres... Being able to do that is what marks out the world champions.

Trending this week

- Car Review

BMW iX3