What's a Le Mans winning Porsche 962C like to drive?

We found out at Goodwood. A 961, too. Time to geek out on two motorsport icons

A paddock full of legends. The cars we all recognise of course, but the drivers, well, they’ve changed. It’s been 45 years since Gijs van Lennep won the Targa Florio in a Porsche 911 RSR, 47 since he won Le Mans in a Porsche 917 KH.

And yet at Goodwood people nudge their children when he strolls amiably past, while the bolder come up proferring posters and pens. Manfred Schurti is here too. His place in my personal firmament of racing drivers is assured simply because he drove the infamous Porsche 935 ‘Moby Dick’ (my favourite race car of all time, and a fantasy I got to fulfil a few years ago) to 8th place at the 1978 Le Mans.

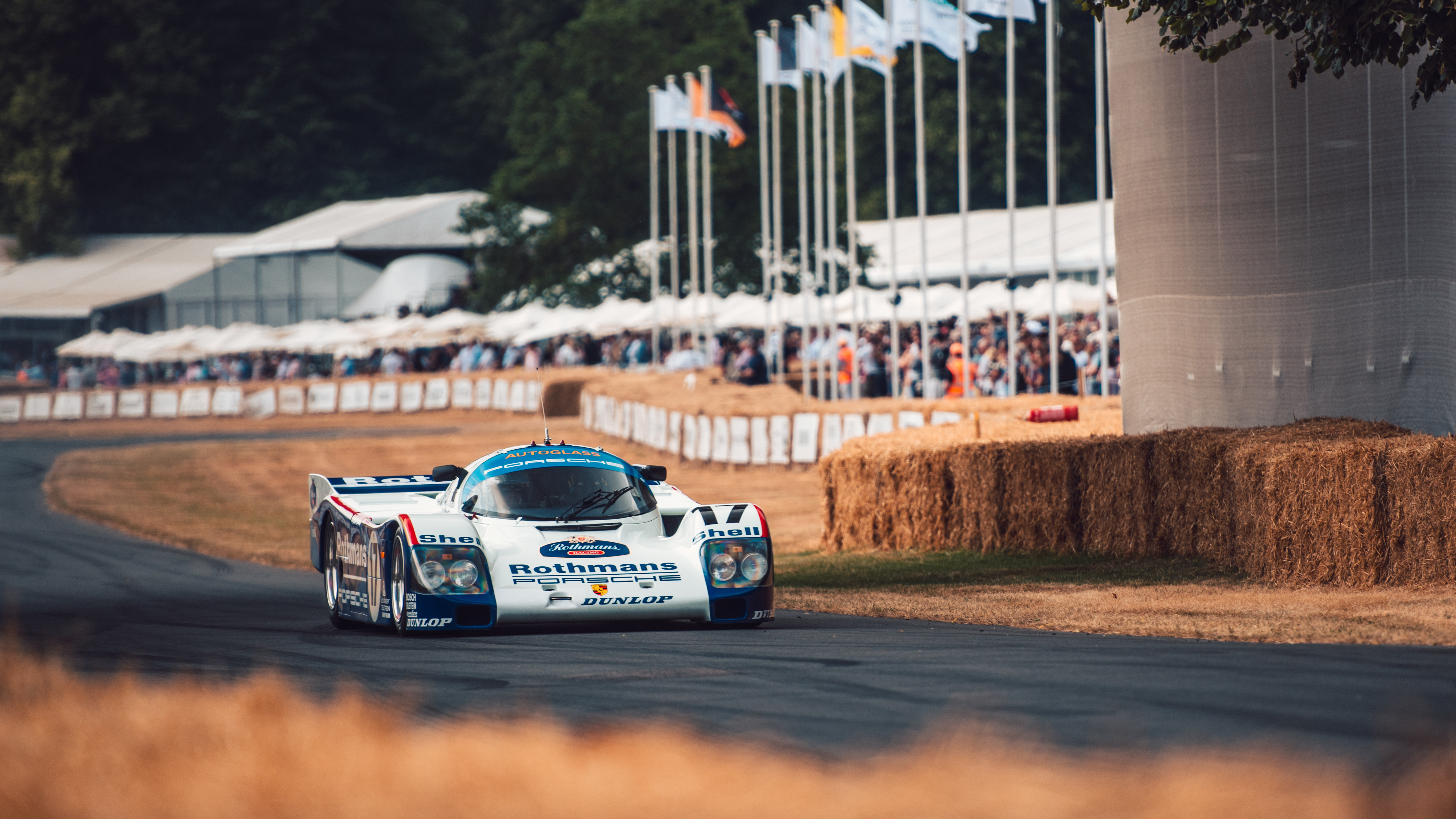

Porsche was celebrating its 70th anniversary at the Festival of Speed this year, and in turn the Festival was celebrating its 25th. It’s easy to dismiss FoS as the same thing every year: same cars, same faces, different sculpture, but this year felt somehow more… uplifting.

It wasn’t just Porsche. The paddocks were bursting with ridiculous machinery, the hill was alive to the sounds of drifting, two-wheeling, autonomousing (Roboracer was fast and convincing, the Siemens Mustang slow and crashy), even jet-manning. His daily flights were absurd by the way – a hovering human lifting off and cruising up and down the main straight, under the bridge to Molecomb corner and back. Forget electric cars, David Mayman’s JB11 jetpack felt like our Jetsons moment, especially when we learned it can climb to 10,000 feet and hit 200mph. Bit on the loud side, though.

In a slight twist to the scheduling, Porsche had managed to convince the Duke of Richmond to allow them to park a load of their most precious and important historics around the sculpture at lunchtime each day. The full parade of Porsches went up the hill, rolled back down to the sculpture, had a ‘Porsche Moment’ (their words, not mine) where banners were raised and fireworks let off into the bright sunlit sky.

It could have come across as dominant, Porsche stamping its authority, but actually it felt rather colloquial, homegrown in a delightfully personal way, with people bemusedly squinting up at faint tracers of smoke flashing through the air. But the best show was on the ground. I couldn’t stop staring: here was Nr 1, the very first Porsche prototype, the car that made this Porsche 70th year.

“We built that car only for experience,” Ferry Porsche once said, “to see how light we could go and how many VW parts we would need”. The answers were 590kg and quite a few. The steering, entire front suspension, cable operated drum brakes and engine were all from the Beetle. Just 39bhp courtesy of the 1,131cc flat four – although that was a 62 per cent boost over standard, Porsche having modified the cylinder heads to accommodate larger intake valves, and raise the compression from 5.8 to 7.0:1. One more thing about that engine: it was in the middle of the car.

Of course there were rear-engined 911s all around, from the very earliest through to the latest GT3 RS and GT2 RS. But mainly it was competition cars. And it was ridiculous: 917, 908, 935, 936 – a paddock full of famous liveries, vast back tyres, flimsy bodywork, beating to a flat six drum.

Top Gear

Newsletter

Thank you for subscribing to our newsletter. Look out for your regular round-up of news, reviews and offers in your inbox.

Get all the latest news, reviews and exclusives, direct to your inbox.

Porsche had got in touch a couple of weeks before to ask if I’d like to drive one of their cars up the hill. A question that needs no answer. Which is why I found myself standing in quite the most amazing assembly area ever. I’d just hopped out of a car and closed the door, which bore the name D. Bell. I happened to look at the car behind, where the actual D. Bell was sitting in a Porsche 804 GP car. No pressure, Derek Bell only won Le Mans five times, and I’m now driving the 962C that he took to victory in 1987 – his last win at La Sarthe. I’m just a little bit speechless. I’m blaming it on nerves. Best not stall when D. Bell will be watching me depart the line.

The 962C is legendary. And worryingly simple to operate. And totally original. God knows what the value is, best not dwell on it. Five speed manual, with dogleg first, 3.0-litre twin turbo flat six developing, well, I don’t bother to ask right then. What I do get told is that the differential is pretty much locked so I should expect it to push the nose through the slow corners and that the gearing is very, very, very long.

There is a row of dials in the cabin, and the right hand one has me concerned. The word ‘Boost’ has been tippexed on. I’m reading it upside down as it’s twisted all the way round to max. 2.8. I’m assuming bar of turbo boost. I leave it where it is. Maybe that’s where it’s been pointed since 1987.

After all, the whole car is entirely original. Which means it’s still running the exact gearbox and gearing it ran at Le Mans 31 years ago. Everyone, including Derek Bell, says it’s lovely to drive. Once you add speed, I’m sure it is.

When I wonder if first runs to about 200kmh (125mph) at the 8,400rpm redline, Armin waves his hand – ‘maybe about that, yes’

What I’m learning is that it’s actually quite an easy car to bump start. I had assumed that at 25mph or so you’d be able to come off the clutch completely. Turns out if you do, you stall. So dip the clutch, let it out and get it fired up again. Armin, the car’s chief carer, had told me the clutch was tough. The whole car is in fact. One of the key reasons the 962 (and 956 before it) were so successful in endurance racing is that they were so robust.

It’s a fabulous car to be inside. You can smell and see the history, the life it’s led is there in every scuff and scratch on the seat and sill, the scruffy steering wheel and faded dash top. You’re not as horizontally positioned in here as in a 917, the driving position is less intimidating. It starts, if you can believe it, on the twist of a key.

I manage to crawl up to the start line without further embarrassment. And I manage to leave the line without issue, too. I reckon I’m 50 metres up the road before the clutch is fully out. Reckoning a bold strategy is best, and knowing the turbos won’t be the most alert, I go immediately to full power. Not much happens.

Not much carries on happening until we approach where I’d be thinking about lifting off in readiness for the first corner. There’s a dim suggestion of whistling from somewhere. But that’s it. The brakes, like the other pedals, are heavy. I turn in, but the car doesn’t really want to. Blame the spool differential. Unless there’s proper heat in the tyres and mechanicals and more speed applied, the rear wheels don’t like rotating at different speeds, so the nose pushes, unwilling to turn. Unnerving.

Corner two is quicker and I’m on the power this time, helping negate the issue. And helping get rid of the lag sooner. I’m on the main straight, and this time there’s more than whistling, there’s its effect, a rapidly gathering thunderstorm of torque and hissing. The flat six sets to work. It makes a dirty, raw noise. Progress, once the rev counter shows 5,000rpm becomes very vivid. 680bhp working on 850kg. Under the bridge it’s getting a proper stroll on.

The suspension is stiff, nodding over bumps, but it feels secure. I’m guessing the ground effect is starting to work. And I’m still not out of first gear. Won’t be for the entire length of the hill in fact. That’s how long geared it is. Armin’s not sure, but when I wonder if first runs to about 200kmh (125mph) at the 8,400rpm redline, he waves his hand – ‘maybe about that, yes’. Second, third and fourth are apparently much closer together. Fifth contains the potential for 240mph.

Driving it up the hill is an honour, a privilege. It’s wildly exciting but bloody nervewracking. How nervewracking I only realise when relief washes over me as I park up in the top paddock. Safe. Done.

It doesn’t stop you wanting to drive again though. Scratching the itch. So later I knock one number off my Porsche racing machine, and head up the hill in another Le Mans legend, the 961. Legend, in this instance, is the right moniker. Porsche built over 90 962s because they were so successful. This is the only 961 in existence. It’s the racing 959, initially conceived to race under Group B regs, but canned when Group B died. It used the same basic engine as the 962, but weighed about 300kg more.

Less daft gearing meant I managed to use first, second and third. It was lovely, friendly, 4WD and easy to see out of. More familiar. Faster up the good Duke’s driveway. But it’s the 962 I remember most vividly. Because it was a historical time capsule. Because it gave me a glimpse of what the men that raced it had to manage. And because the man that raced it was parked behind. Man and machine: legends both.

More from Top Gear

Trending this week

- Car Review

BMW 1 Series

- Top Gear's Top 9

Nine dreadful bits of 'homeware' made by carmakers