What's going on at Brit start-up Arrival?

Arrival plans for an all-electric sustainable future – we've driven its van and seen its future car project

Is it possible that vehicles we don't much like will provide the impetus for the next generation of cars we do love?

This is Arrival, a fascinatingly different start-up company that's on the point of launching an electric delivery van. Soon after will come a city bus. Then a car for Uber. It's also working on autonomous drive. None of these are, in the world of TopGear, remotely sexy.

Still, I have a sneaky suspicion Arrival's techniques and cleverness could be subverted to do what is so hard for the conventional car industry to do: build individualistic and interesting cars that go beyond mass market blandness.

Arrival's mission is sustainable vehicles, made with low investment. In the rest of the motor industry, the R&D and factory costs are a brutal hurdle for any new, er, arrival. So Arrival has rethought the lot.

Its van has got huge delivery companies such as UPS (which fed into the design) very interested. This in an age when most of us are getting far more stuff delivered. With so many vans pouring onto the roads, it's vital they're sustainable, safe and cheap to run too.

Driving conventional diesel delivery vans is a bit grim. They're cumbersome, noisy and surprisingly hard to see out of, and often have few assistance systems. Comfort when driving isn't great, and in a delivery job you have to keep opening a heavy door and clambering up and down to the driver's seat. And they pollute.

I tried the Arrival van you see at the top of this page. It has a sliding door on the kerbside, which you can leave open in low-speed work. The floor, with no engine to distort it, is low and flat. You simply walk in and take your seat. Visibility is unbelievably good via giant glass and 360-degree cameras. The interface is on a screen, and straightforward. There's another door through the bulkhead to the cargo bay, so you don't have to walk around the vehicle and climb up there to fetch the parcel you're about to deliver.

It has a 204bhp front motor – twin-motor 4WD will be available too. Anyway, the single one is plenty for me when driving unladen around an industrial estate in Banbury. It accelerates smoothly and quietly. It steers straightforwardly, and rides well because, almost uniquely for a van, it has independent front and rear suspension. The brakes aren't properly calibrated yet, so my apologies to the Arrival PR person who I all but hurled through the windscreen the first time I slowed.

Arrival has designed its own motor and controller, and the battery and its management and the electronics. They're adaptable to go into the bus and car too, spreading the cost. The battery is modular, with WLTP range in the van from 112 to 180 miles. Sounds plenty. You try driving 112 miles in a day while stopping every five minutes to ring a doorbell, wait, drop the parcel and get a signature. Or trying again at the neighbour's.

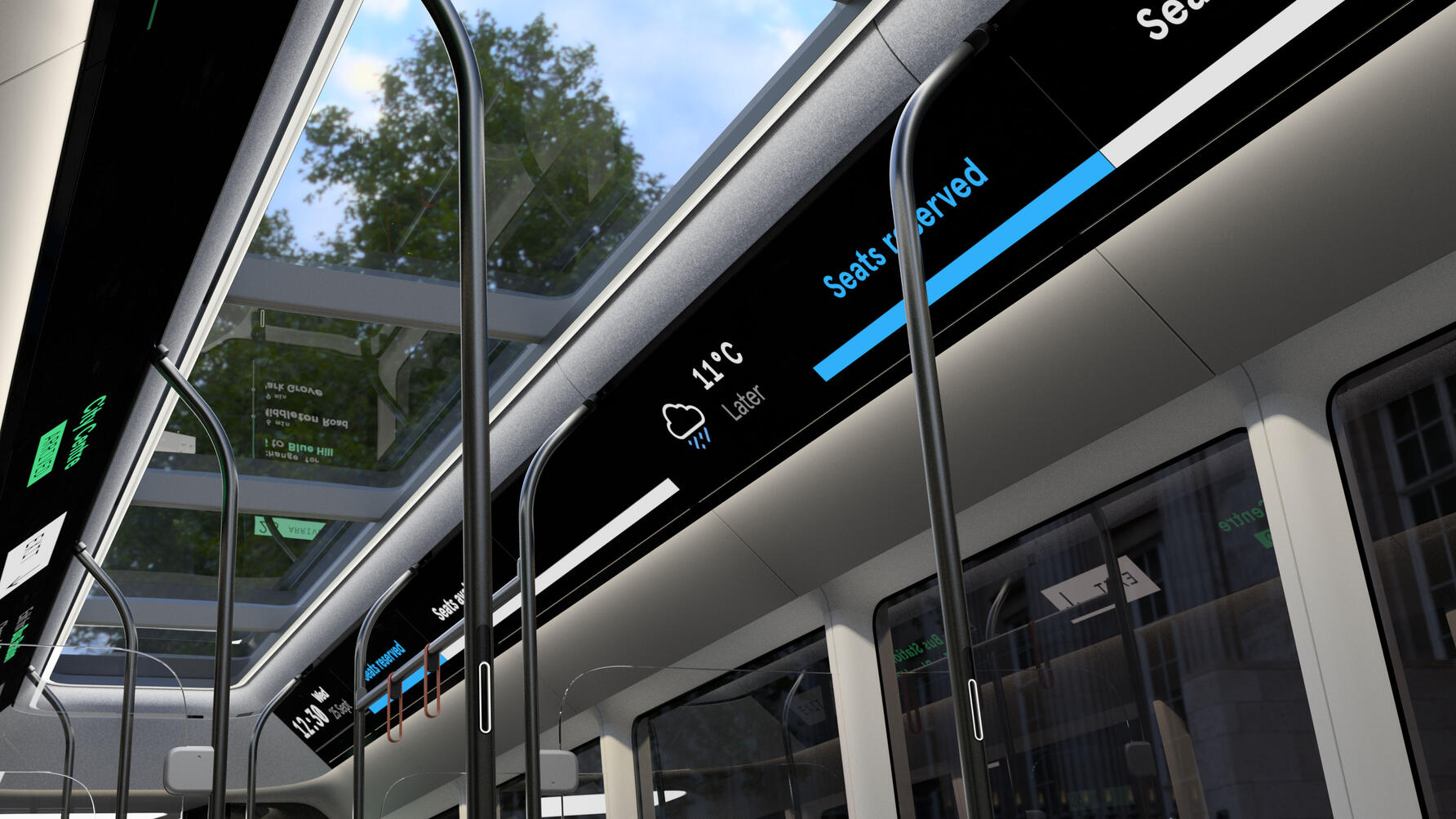

The bus then. (Soz, told you we had to plough through some not-really-TopGear vehicles.) It too has a low, flat floor, plus dropping suspension for accessibility and an airy interior. I live in London so ride on buses a lot. This one is much nicer.

Top Gear

Newsletter

Thank you for subscribing to our newsletter. Look out for your regular round-up of news, reviews and offers in your inbox.

Get all the latest news, reviews and exclusives, direct to your inbox.

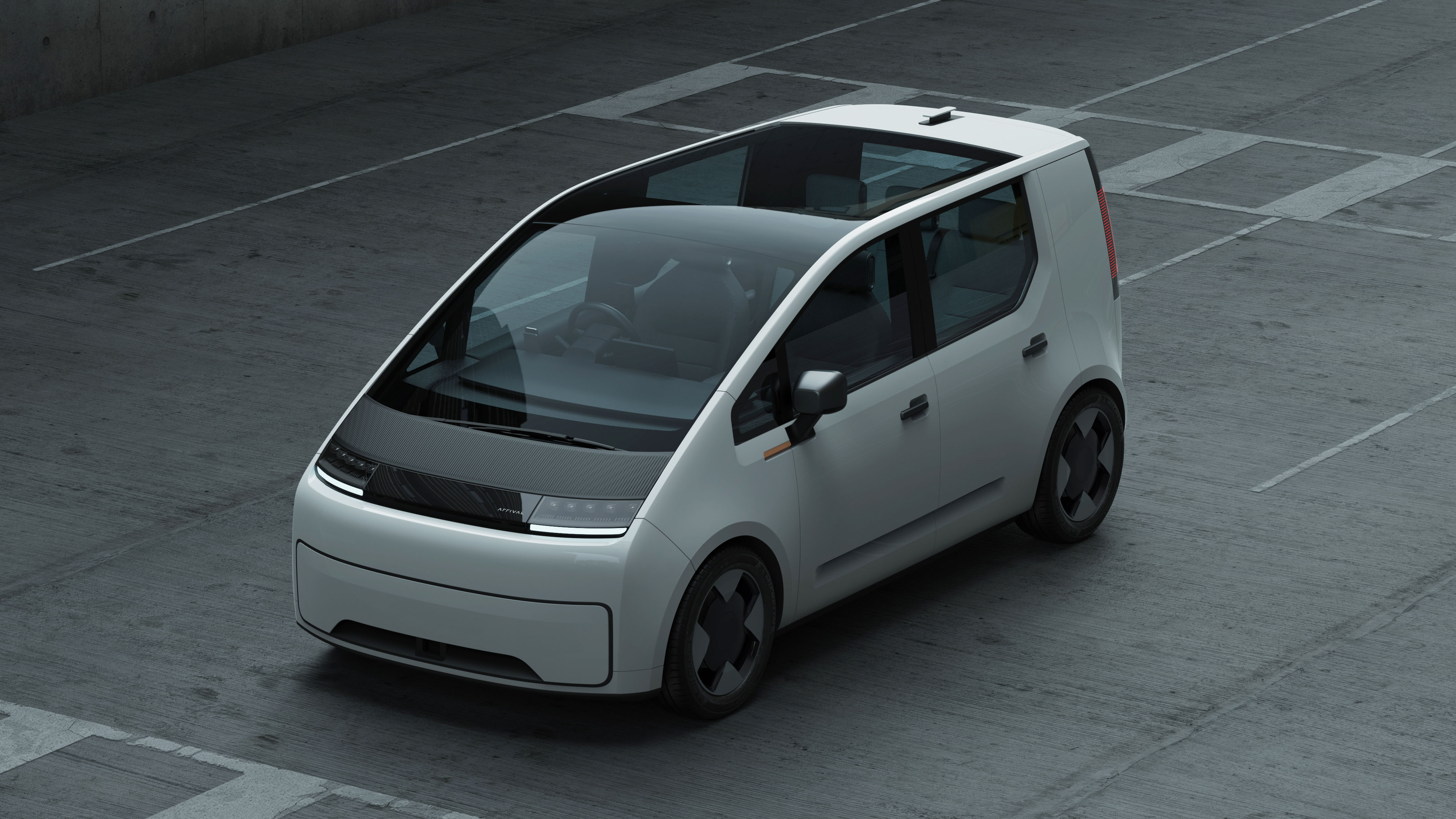

Arrival's car is due late next year. It looks like a supersized shovel-fronted VW Up. In a good way. It's been developed in partnership with Uber. But it can't be a pure purpose taxi. Uber drivers also use their (mostly Prius) cabs as family cars when off duty.

Even so you can see how the taxi bit takes priority. The back seat slides into the boot and the front passenger one slides forward, giving S-Class rear legroom in a Golf's overall length. Upholstery and the floor are easily cleanable after passenger… upsets. Accessibility is superb.

Driver comfort matters hugely. For the van it's a matter of productivity as well as welfare. In the car, because the individual drivers own it and drive an average 30,000 miles a year, it's a matter of getting them to choose the Arrival over a Toyota.

OK, but how can a company you've never heard of get three vehicles onto the market in three years? Especially when the Ford Transit, the Mercedes Citaro and the Toyota Prius aren't exactly pushover rivals.

The answer is by being agile, industrially speaking. Three colossal costs for a conventional vehicle factory are the metal stamping line, the body welding line, and the paint shop. Arrival's 'microfactory' goes without each of those.

The body panels for the car, van and bus are made of a unique sandwich of glassfibre mat and woven polypropylene. They're put into a cheap mould and heated until the polypropylene melts, then cools and sets. The result is robust and corrosion proof. More layers can go into the mould at the same time, for instance the trim cloth for a door or a headlining, or paint if the buyer wants it.

These panels mount to a vehicle frame of largely extruded aluminium. Again, cheap and simple to tool and build, as Lotus and others have proved.

To put these together with the mechanics and electrics, Arrival has another triumph of intelligence over industrial muscle. Artificial intelligence in this case. The microfactory has no production line. It instead uses dozens of Arrival's own little wheeled pallets, called autonomous mobile robots, or AMRs.

Sure the microfactory does use a few conventional big arm robots to join and assemble the parts, but it's the dozens of little AMRs that are the breakthrough. They collect and bring in the parts, and can move in any direction. They will avoid each other as they move, gradually figuring out their own optimum paths though the factory. They communicate with the factory's cloud. They'll swarm together to move big and heavy parts. They react to changes in the plant, minimising their use of energy and time. They have "a primitive brain and cortex".

All of which means a tremendously flexible system. Each microfactory can build multiple kinds of vehicle. Also the microfactories don't need special buildings – any light industrial box will do. They can pop up in no time. The vehicles will be made near where they're sold. Arrival already has sites in Oxfordshire and South Carolina.

Since its founding in 2015, Arrival has got big investment behind it. Hyundai-Kia is among those to have done their due diligence. The carmaker put in £80m-plus two years ago. (That said, Arrival shares lost 90 pecent of their price in a year. Not unheard-of in this field actually.)

A £40 million microfactory, tooled up with its AMRs and 300 humans, will build 10,000 vans a year. Trust us, that's a miniscule investment. The electric van's price will be no more than a diesel equivalent, says Arrival, and it'll be vastly cheaper to run. The same sort of AI development that powers the microfactory will also support connected, predictive maintenance to keep the vehicles running for longer. And, later, autonomous driving for the vehicles themselves.

So, if it eventually flourishes, I wonder if we can persuade Arrival to build us a nifty lightweight electric sports car?

Trending this week

- Long Term Review

Life with a 500bhp BMW 550e: do you really need an M5?