Taking on Namibia in TG's Project Swarm

It's been months in the making, but our own desert runner takes on the sand dunes of Namibia

It’s 4am and freezing bloody cold. I’m not-sleeping in a dry hitch of the Ugab river in Namibia, badly wrapped in some sort of tarpaulin body bag, dusty, smelly and the kind of happy that makes your heart hurt. Yes, there’s a rock poking my kidneys and something furry keeps grunting from the brush 30 feet to my left, but, my God, when the stars look like this, it’s impossible to be voluntarily unconscious. In fact, this is way past the jurisdiction of the normal and well into the glittering realms of fairy tale. Earlier on, the burning ruins of a sunset collapsed into the flat black velvet of night-time, and then the stars exploded. Without the fuzzy filters of pollution – light or atmospheric – to mantle their shine, they are twinkly shards of pure, distilled awe. I look over at my truck, and allow myself a smile. We’ve come a long way, this pickup and I.

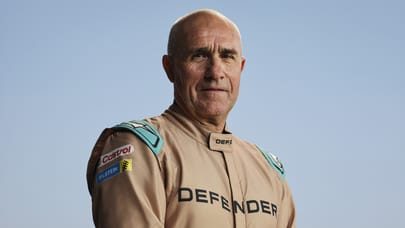

Words: Tom Ford / Photos: Rowan Horncastle

I ponder some more on this the next morning while taking care of my morning ablutions away from camp equipped with a hygenic shovel. Because I find, disturbingly, a clear trail of paw prints in the soft dust about 30 feet from where photographer Rowan and I were sleeping out. Now I’m no Attenborough, but I’ve seen those prints before. Except they were made by my pet cat, and they weren’t the size of a damn dinner plate. Confirmation from guides Paul and Michelle – a large male desert lion has circled us as we slept, conveniently ignoring our perimeter lights. Later, we hear the lions huffing in the distance, big, basso coughs that carry through the river bed. I am unbothered. It’s easy to be brave in retrospect.

Still, large predators aside, it’s been lightly epic so far, and not just because the journey has been months in the making and miles in the doing. Indeed, over a year ago we decided to build an adventure truck from the solid and utilitarian base of a Mitsubishi L200. What came out the other side, thanks to a team of very clever, creative and obligingly co-operative people, I christened Project Swarm. A kind of European take on a pre-runner desert racer, but which also carried a survival-style moped, and had an aeroplane wing mounted on the back as a hangar for drones. It also got a PPC external roll-cage, 35in tyres and Speedline wheels, military-spec SuperPro suspension, rear-mounted spares, Dakar-style Cobra seats, an on-board compressor, a winch, a wide-arch treatment and enough Lazerlamps LED lighting to temporarily blind West Africa, but more on that later. What it didn’t have, and the point of the month-long ship trip to Namibia, was a real test of its capabilities. To be honest, it looked a little out of context where I live in Lincolnshire.

Not so now. We arrived in Namibia to find Swarm freshly unpacked from its shipping container and ready for action. A few tweaks – mainly to tyre pressures and the webwork of straps and ratchets that keep everything shipshape – and we headed out. First bit, no problem. I’m used to the truck on the road, and while it’s not actively hard work, it’s got shades of very early Porsche 911 in the handling. As in, with all that weight held high and rearwards, it tends to want to triple-Salchow its way into the scenery if you get too enthusiastic with cornering speeds. But, hey, we have time, so it’s a leisurely dawdle for the first few hours.

A few stops for supplies and on to top up the tanks and cans with fuel and you realise that a truck like this in Namibia is a bit of a rock star. Tough is good in a country with this much wilderness, and Swarm certainly looks macho enough to please. Petrol attendants (you don’t self-serve here) flock, selfie the hell out of it and beam like crazy just to have it in the yard. One person offers to buy it on the spot, and we spend a good 20 minutes fielding questions. Finally, a place where people appreciate my overkill. It’s a feel-good start.

Soon enough though, it’s off up the Skeleton Coast on normal roads and some sections of pretty beach – past shipwrecks, seaside and grumpy seals – and heave right onto sand and gravel roads. First test, and a tough one; these roads have washboards eroded into their blank faces, and they are as unkind to suspension as it’s possible to get. As in, shake-everything-to-bits unkind. Your eyes blur, the whole car shimmies like a sub-bass jelly. Anything in front produces a half-mile dust storm behind it – so you can’t follow close – and if you catch the edge of a rut the car will kick sideways in a fantastically scary way. Apparently, if you drive above about 75mph, you can mitigate the vibration, but then you catch an edge and slow down for fear of barrel-rolling down an endless barren vista. White knuckles become the norm.

After a few hours, you get almost used to it, but it is the very definition of tiring, and we have to stop regularly to make sure the kit is still attached to the truck. But, so far, so good. We pause to help out some tourists in a Hilux who have suffered a puncture and are standing in a disconsolate ring, staring at their hopelessly weedy-looking bottle jack – which, as they have discovered, is pretty much useless if your car has big tyres and a slight suspension lift. So we unhook our big Hi-lift and help them get on their way. Samaritan points achieved, we head to a huge russet outcropping in the far distance. There is already sand and dust in places where there should not be sand.

The truck, it has to be said, is bloody awesome, and not just because it looks like something a sugar-high child would draw with a crayon. The suspension, while not sophisticated, is polybushed and heavy duty, and we’re permanently carrying a full load (Swarm is pushing the full-load limit at all times, in dynamically interesting ways), but big, aired-down tyres and tough underpinnings mean we float where others thump. No, it’s not the last word in handling, but the 35s don’t even rub much off-road on full compression – a testament to the work put in cutting back the sills to accommodate them. The noise from both the snorkel just beside the driver’s window and the exhaust (complete with incessantly rattling flappy trucker tip) is an industrial whoosh and turbo hiss that speaks of reliable, grunty power. We may not be fast, but we feel pretty much unstoppable.

A feeling that continues a day later when we drop into the Ugab River basin itself. And water. Now, for some reason, I wasn’t expecting any water apart from the actual sea – hence the snorkel – but the channel sections of the Ugab have plenty of small rivers running through them. Thus we find ourselves rolling through narrow corridors of vegetation that cling to the edges of the life-giving flow. Nothing past about a metre deep, no problem for a truck as tall as Swarm, but you have to watch out for sunken potholes and make sure you leave your doors open if you stop: lions hang out here, so you need to be able to get back into the car quickly unless you fancy becoming a gory statistic. It has happened. It’s beautiful, though, in the way that Africa manages to be both harsh and unforgiving, yet majestic. Some of it, especially the big rock formations – and this sounds ridiculous saying – is so utterly African, it feels a bit Disney. I’ve watched so many TV shows about this kind of place, watching baboons skitter away up a rockery at our approach feels a little surreal.

Soon enough, though, it’s time to make camp, and we erect a windbreak, build a fire and break out the food. As the sun starts to fade, we unload the MotoPed for a little light scouting in places where a big truck can’t go. It is at this point that I have to admit I can’t ride a motorcycle. At all. I never learned, haven’t bothered, and only know the theory. Which – let’s face it – only takes you so far. Still, I have a sense of balance and solid understanding of machines, so I clonk first and head off, slightly confused by a second gear that’s hard to find when your foot fulcrum is a pedal that moves. I make it approximately 300 yards before attempting to ride over a football-sized elephant dungball and smashing face-first into the floor. Luckily, my inexperience means that this glorious dismount was achieved at less than 7mph, albeit in an optimistic fourth gear, and so the only thing bruised is my ego. And face. After every single person in our group demonstrates greater skill on the ’ped, I decide I’m much more attuned to something a bit more solid, and fire up Swarm’s Lazerlamps lighting array, neatly banishing the encroaching darkness in a solid corona of ultra-LED daylight.

Top Gear

Newsletter

Thank you for subscribing to our newsletter. Look out for your regular round-up of news, reviews and offers in your inbox.

Get all the latest news, reviews and exclusives, direct to your inbox.

Jesus. The light from Swarm is ice-bright and clean. Surgical and clipped. So unlike the messy, organic, wandering warmth of the moon and stars. And it redacts the detail from the big views, leaves you with stark images of the rocks hundreds of yards away. It’s like having your own power station and attendant floodlights. And the terrain becomes even more otherwordly. This is not grandeur. This is where the intellectual oxygen is pretty thin, and you’re back with pure, childish wonder. And from the drone – launched from the rear wing – our little blue truck tracks through the depths of the night like some bizarre diesel-powered sea creature. It’s really weird, and wonderful, and utterly without equal. We go looking for elephants, and see many things – kudu, jackals, more baboons – but at 3am or 4am, we admit defeat, roll back to camp and fall into our tarps. Which is where we came in.

Next day, we cover distance. Through gorges and more water, across dusty plains whose only defining features are a haze of heat and a general feeling of inhospitableness. There are rock crawls, and a couple of little hills that flump into silty sand that has the texture of oil between the fingers, and manages to huff completely through door seals like the ghosts of adventures past. Swarm just keeps on keeping on. We launch the drone, and see new vantages. It’s a country that delivers more with every mile, every corner, every crest. It’s beautiful, and vicious. Eventually we hit more gravel roads, and Swarm behaves a bit… oddly, pulling left when braking. Convinced I’ve somehow managed to fill the rear drum brakes with soft, insidious dust, I carry on driving for an hour or so. And then the front wheel falls off.

After debating what might be wrong with the truck for about 50 miles, co-pilot Conor casts a casual glance out of the window and makes it clear that we probably better stop. As fast as possible, but in no way violently. Like, now, but slowly. Upon investigation, it seems that the rough roads and a few hundred hours of GBH have managed to rattle loose the bolt that held the top of the wishbone. No actual damage, but also no actual bolt, and thus an unsprung mass held on by the bottom strut and hope. Erp. The support car is despatched, and our guide Paul comes back an hour later with a scavenged bolt roughly the right size; a bit of creative jack-work, some shuffling and a few swear words later, and we’ve got a double-bolted top wishbone that’s probably stronger than the original set-up. “Simple is best” as a life lesson.

Soon enough, it’s put to the test. We need to cross a small set of hillocks to our next destination, and Swarm feels quite epically uncomfortable on sideslopes, let alone sideslopes with rock steps and a tumbly drop on one side, with some decent turns to make on the way. Diff lock in, low-range, diesel gassing mightily, we hoof up the scary bits, front wheels kicking into the air, me swearing and sweating and feeling my stomach heave. The car never stops, never gets stuck, but when asked to return the journey for more pictures, I have to decline – it just feels like a bit too much pushing of luck. And there’s another reason: I’ve just seen what’s up ahead, and it’s our final test. The dunes. And these are the biggest in the world.

A horizon so blue and featureless that it feels like you could just fall off into the sky. The weight of the view pressing down upon your senses until you’re sure your ears are going to pop. It looks like adventure. Heroism. Grand derring-do. It’s also looks thirsty and barren. And… massive. For the first time, our big, macho truck becomes insignificant – a little blue dot on a golden sea. And a sea is a proper analogy, because this is a place of waves, and crests and tides. And if this is a sea made of sand, it pays to beware the currents.

See, the thing with crossing many miles of dunes is that you can’t just charge off in any direction you like. You have to sort of flow with the landscape. Fight it and you’ll get stuck in short order. Try to dominate them by charging about, and the confusing banquet of optical illusions will have you sending a truck off a 150m dune at 60mph. It’s not the jump that will get you; it’s the landing. But you need momentum and wheel speed. You need to slingshot massive bowls just to get enough speed to make it out the other side, you need to work with gradients and slipfaces, and be able to read the sand – textures, colours, shadows, even – like Paul. I can’t read the dunes like Paul. I get stuck a lot. Stuck but not stopped. Because Swarm’s tyres are big and aired-down to grippy squish, and because we are equipped with the right suspension, our pauses and retries are down to driver error rather than hardware more often than not.

And there are interesting facts. The slipfaces of the dunes with this kind of sand never breach 38 degrees, and even though it feels like you’re falling down the sides of them, you can brake as hard as you like, and you stop instantly. You just have to always follow the weight down the hill – and never, ever try to turn the car when you’re at an angle unless you’re moving quickly. After all, “weight always wins” – and you’ll end up flopping over in short order if you ignore the rules. And even though it looks like the world’s biggest playground, even if we’re here with people who know exactly what they’re doing, if you screw up, you’re a long way from a hospital. You can fall in love with the view, but just remember that the best you’ll get back is indifference.

But you’ll get it. And you will fall in love. Because when you get out into the big dunes, the really big backcountry dunes that sometimes manage way more than 300 metres tall, you’ll get to the top and feel instantly promoted to the post of tiny god. When “epic” seems like a tired, overused and too-small word, you know you’re in the right place.

We spend much time trekking across the dunes. And it never – not even slightly – gets boring. There’s a surprising amount of wildlife, from dew beetles in the sand, to flocks of pelicans and flamingoes scudding across the sky. There’s always a new place to challenge yourself, and the truck, so many things to learn. We go a little too fast over one dune and discover that Swarm pulls what can only be described as a massive wheelie. So I try it again, and again, until we’re going so fast that we launch off into the air like some great blue albatross – the rear wing finally back in freefall where it belongs. The landing is hard and so is the laughing – this is what we came here for: to test to the extreme, and learn, and adventure. And after several days of traversing Namibia’s mind-boggling countryside, we finally, eventually, ride up from the depths of the dunes and come back to the sea at sunset. And the horizon blazes back at us like a silent apocalypse.

And so it finishes. From the germ of an idea, a sketch on a scrap of a paper, to a breath-stealing sunset from the top of a skyscaper dune on the other side of the world. We’ve taken a normal, standard truck, and gently remade it into something that can take on anything. Plenty of people had a hand in making it work, and to them, I offer my thanks – Project Swarm is undoubtedly a success. It’s not been easy, but as they say, straight roads never make for skilful drivers. But as we pull back from the edge of the last dune and start back to civilisation, I realise that’s what this is all about: keeping going, following through. Adventure isn’t about having a truck like Swarm. It’s about being open to possibilities. After all, a dream only remains a dream if you don’t do anything to make it real.

Trending this week

- Car Review

BMW 1 Series