Masterminds: thinking like a champion

What can we learn from the unconquerable minds of motorsport?

“It has been my dream, my ‘one thing’ to become Formula One World Champion. Through the hard work, the pain, the sacrifices; this has been my target. And now I’ve made it. I have climbed my mountain. I am on the peak.”

As Nico Rosberg settles into retirement from F1 this Christmas, he can stand back and admire the views that come with conquering motorsport’s steepest summit. The ascent took in 23 grand prix wins and one gruelling world title; ahead lies a lifetime together with wife Vivian, and daughter Alaïa. What an achievement. What a reward.

Words: Joe Holding

Photography: Dunlop, Colin Turkington, Oli Webb, ByKolles Racing, Signatech Alpine/DPPI, iomtt.com, Dave Kneen/Pacemaker Press International & others

The idea of Rosberg emulating his world champion father sits uncomfortably with some, largely because of a (let’s face it, well founded) belief that his talents don’t measure up to those of Mercedes teammate Lewis Hamilton.

With more victories, more podiums and an average qualifying advantage of nearly a tenth and a half in 2016, there’s no denying that Hamilton is the faster driver. But this is motorsport: it isn’t always fair. A string of reliability problems and bad starts put the Briton on the back foot this season, and his rival took full advantage.

In the build-up to the grand finale in Abu Dhabi, Rosberg’s good fortune sparked a debate about whether or not he was ‘worthy’ of being a world champion. To put the matter to bed, he is as worthy as they come. End of.

The German – “a tough little bugger” in the eyes of former team boss Ross Brawn, speaking in a recent interview with The Telegraph – has emerged from his tribulations as a figure of incredible tenacity. Rosberg suffered defeat after defeat at the hands of his childhood friend over a period of 18 years. The latest of those – at the 2015 US GP in Austin, Texas – was compounded when Hamilton tactlessly threw the ‘2nd place’ cap into the lap of his devastated teammate. Unintentional it may have been, but the metaphor was clear.

The cap, unsurprisingly, came back at Hamilton, as did Rosberg. The whole ordeal motivated him to redouble his efforts behind the scenes, and a run of seven consecutive wins thereafter coincided with Hamilton not taking a chequered flag again for eight long months.

Resilience underpinned Rosberg’s performance, and in many ways his success this year has taught us more about a champion’s mentality than if Hamilton had clawed a fourth world title back from the brink in Abu Dhabi.

And that’s important, because everyone from the die-hard disciple to the casual fan has an innate need to see underdogs pull through.

Think back to Niki Lauda at the Italian Grand Prix in 1976, barely a month on from the horrific crash that nearly killed him. Or to Ayrton Senna’s maiden win in Brazil in 1991 when he battled to the finish line in an ailing McLaren.

Top Gear

Newsletter

Thank you for subscribing to our newsletter. Look out for your regular round-up of news, reviews and offers in your inbox.

Get all the latest news, reviews and exclusives, direct to your inbox.

In this regard, motorsport makes no greater contribution to the public conscious when its protagonists triumph over adversity. It’s a subject in which Nico Rosberg is a remarkable case study.

***

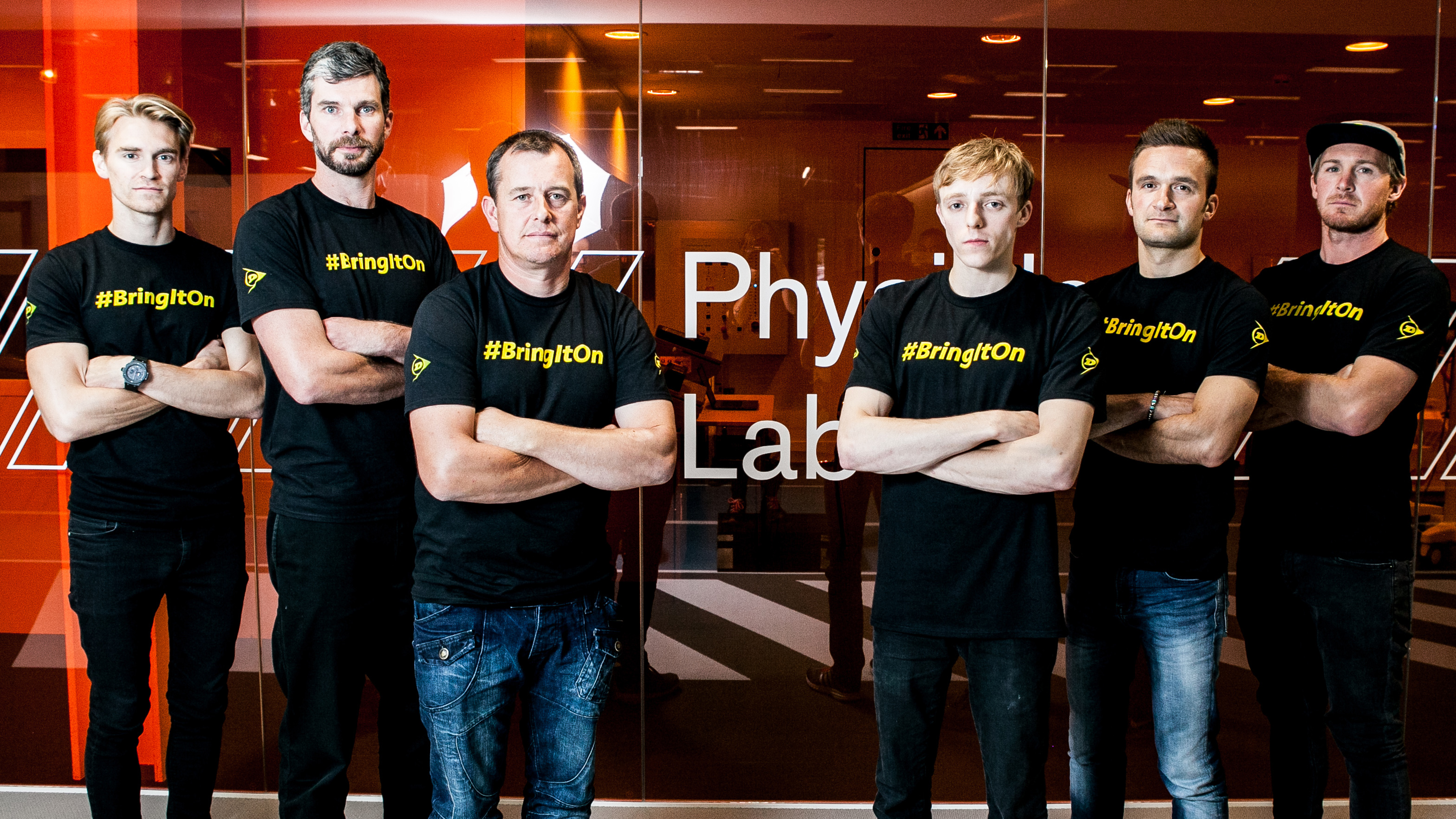

So, what can everyday folk like you or I learn from the mental feats of motorsport’s elite performers? As luck would have it, TG was invited to GlaxoSmithKline’s Human Performance Lab back in September to take part in Dunlop’s annual Mindset Challenge, the focus of which this year was understanding how top athletes respond to stress and anxiety.

Those athletes consisted of climber Louis Parkinson, big wave surfer Andrew Cotton, downhill skater Pete Connolly, and from the world of racing, European Le Mans Series champion Oli Webb, double British Touring Car champion Colin Turkington, and Isle of Man TT legend John McGuinness.

Facing them – and acting as the group of unremarkable ‘non-athletes’ – would be a selection of journalists, including yours truly. The name’s Joe. Average Joe.

“One of the things that’s really hard to do in a lab is to test people under real emotional conditions,” says University College London’s Professor Vincent Walsh, who designed this year’s study. “So what these tests have been developed to do is to induce emotional states to tap into the emotional system. That then allows us to look at people’s perception and memory performance under different emotional inductions.”

These guys are all abnormal. They're all more obsessed than the average man in the street.

The tests in question would utilise the International Affective Picture System: an archive of unique images, assembled by the University of Florida, which is used to stimulate positive and negative emotions.

By exposing participants to short bursts of the specially chosen images on a computer screen, it is possible to activate areas of the brain just as would occur in real world scenarios: imagine the fear of going flat through a blind corner, or the pressure of a do-or-die qualifying lap. Specific details about the photos are strictly forbidden from entering the public domain, but be in no doubt that they really work.

A series of repeated challenges follow each batch in quick succession, from which Walsh and his team can measure a number of variables such as reaction time, accuracy and an individual’s ability to regain composure under pressure.

Immediately there is an eagerness among the non-athletes to discover any hidden potential that might add weight to the old ‘I could’ve turned pro’ chestnut. However Walsh laughs off the suggestion, assuring us that the practiced hands will come out on top with a significant margin.

“These guys are all abnormal. In a great way,” he explains. “They’re all outliers: they’re all faster, more accurate, more perceptive, more determined. They’re all more obsessed than the average man in the street. That’s why they are world beaters.”

And what can the world beaters teach us? “We’re all faced with stresses, we’re all faced with things that disgust us, that anger us, that scare us. And maybe learning something from these guys will help us get over these things.”

An interesting hypothesis. More on it later.

***

In motorsport adversity takes many forms, and the highs and lows have a very real impact on those at the heart of it all. In 2009 Colin Turkington was on top of the world when he won the British Touring Car Championship for the first time, surviving the late onslaught of three consecutive wins from title rival Jason Plato at Brands Hatch to take the crown by just five points.

However, it was a title that Turkington would never get the chance to defend. Far from ‘doing a Rosberg’, his absence the following season was enforced as his team’s main sponsor pulled out, leaving them short on funds and their star driver short of a seat.

“I put the work in, fulfilled the dream,” says Turkington, “but the following year I found myself without any racing at all. So I’d just delivered the best season, won the championship, but then had no drive. So I was on the sidelines.

“That was really difficult to take, because I almost felt like I’d done something wrong. And then you start to think to yourself: ‘I’ve been out of this for a year, if I come back in am I going to be up to the standard that I was when I left?’ So you start to get all these doubts and negative thoughts. That was a particularly difficult period.”

Bloody but unbowed, Turkington made his full return in 2013 and was champion again the following season. His rise, fall and subsequent re-emergence embodies the brutal nature of the BTCC.

The application of success ballast – an evolving weight penalty that slows down the frontrunners – ensures that drivers can be winners in one race and backmarkers in the next. In such a chaotic environment, Turkington often finds himself zoning in on the job at hand with the mantra “every point counts”.

“Particularly if you’re in the middle of the pack, there is no let up,” says the 34-year-old. “There’s a lot of information to process alongside your own car while trying to go as fast as possible.”

Unsurprisingly, crashes are common, and most of the grid can expect to pick up a DNF or two over the course of the season. What really hurts, Turkington explains, is when the setbacks are self-inflicted. Frustration is a dish best served by someone else.

“But with us having three races in the day, you have to quickly put it behind you. You know that your next opportunity is just round the corner.”

That isn’t the case in the World Endurance Championship. With only a handful of opportunities to put points on the board, title challenges can implode with only the slightest errors. The pressure to deliver puts an immeasurable burden on those behind the wheel which, drawn out over several hours, makes each event a punishing experience.

Oli Webb – an LMP1 driver for privateers ByKolles Racing and previously an LMP2 driver for Signatech Alpine – has an intimate understanding of what is required in this discipline of racing.

In 2014, the fell clutch of circumstance ensured that he and Signatech went into the final race of the European Le Mans Series with a nine point lead over Jota Sport at the top of the standings, despite the rival entry having secured four out of five poles in qualifying that year.

“The pressure that was involved in that last race was incredible because I did the last two stints,” says Webb. “It was in a way the hardest two stints I’ve ever done because every single second of the strategy between us and them was dependent on whether we’d come first in the championship or second, which in my head was just nothing. I didn’t want to come second.”

In the end it was indeed Signatech who prevailed, and two years on Webb finds himself in an LMP1 seat in the top tier of prototype racing, albeit with a sizeable deficit to the likes of Porsche and Toyota.

Not that that’s any excuse to give in to the manufacturers. A modern approach to sports science recognises that physical and mental performance are inextricably linked, and that valuable time can be found on the track by correctly preparing drivers away from it.

Mind coaches and heat chambers are just two of the measures employed by teams to keep their line-ups in shape, while at Le Mans special night glasses are used by some to aid tired eyes during the darkest hours.

Races like Round 6 of this year’s WEC in September is where the hard work really pays off. Operating with a cockpit temperature of 44 degrees Celsius at the Circuit of the Americas in Austin, Webb says he lost 7 kilos on race day alone as temperatures in the region soared.

“I found myself for the first time – I think ever in a car actually – genuinely mentally deteriorating to the point where I was really struggling to focus,” remembers the 25-year-old. “I saw a couple of the drivers in the paddock falling onto the floor. When your mental state gets affected, you know you’re physically really drained.

“But when you start physically running out of energy, that’s when your mental strength will kick in. It’s your ability to overcome the strength you are losing.”

This ‘mind over matter’ quality is required in spades at the Isle of Man TT. From the outside looking in, the unthinkable level of speed on virtually unaltered public roads makes it one of the most terrifying races in the world, of the sort only a lunatic would enter.

John McGuinness is not a lunatic, but that doesn’t hold him back. A winner of 23 TTs, he is the second most successful rider in the history of the event behind the late Joey Dunlop, who won 26.

In the 44-year-old’s own words he has “nothing left to prove”, but being so close to becoming the greatest TT rider of all time is, for now at least, providing enough motivation to dispel any thoughts of retirement.

“I think there will become a point, and I’m hoping it’s pretty soon,” says McGuinness, reflecting on the idea of calling it a day. “Law of averages or whatever you want to call it, they’re going to get you eventually. And I’ve done a lot of laps: the window is getting smaller now.

“But I still feel good, I still feel sharp, I still feel strong... And the fire is still burning. That’s the problem. It’s a bit of a drug really. The Isle of Man won’t let go.”

Logically fear should make it easy to walk away, but a common trait among racers is the ability to put negative feelings to one side. Tellingly, if you ask McGuinness about what scares him, he won’t talk about crashes or injuries, but instead about failing to get good results. It’s what sets his ilk apart.

The fire is still burning. That’s the problem. It’s a bit of a drug really. The Isle of Man won’t let go.

That isn’t to say he finds himself unafraid when lining up before a race. “It’s funny, it comes in stages,” he observes. “Something will hit you. It never goes away, that fear. It’s tough. We’re threading a needle through the streets at 180-190mph, but it’s all in control in my eyes. The layman looking at it can’t get their head around it. Their brain can’t compute it fast enough, but I feel like I know what I’m doing.”

“It’s a case of ‘the Is are dotted, the Ts are crossed’, I’ve set the bike up as best as I possibly can... I don’t think: ‘This guy tapping me on the shoulder might be the last person who’s ever going to touch me.’”

When it comes to the Isle of Man TT, the subject of fatalities is one that’s impossible to ignore. Five people were killed out on the Snaefell Mountain Course in 2016, the joint-deadliest year for the event since 1970.

These days riders are consulted more than ever when it comes to safety measures around the 37.73-mile circuit, but as McGuinness puts it, all the precautions in the world won’t “make the walls any softer.”

And ultimately, those who take to the course are doing so of their own free will. As with any form of motorsport, accepting the risks is a prerequisite of taking part.

“I think we’re hardened to it,” concludes McGuinness, who has witnessed several friends perish during his two decades competing in the TT. “Something in your brain just thinks it isn’t going to happen to you.”

***

Three weeks later the test results arrive via email, and it’s striking how McGuinness’s closing words translate into the raw data produced in the lab.

The athletes – as expected – wiped the floor with the journalists, displaying a 10 per cent speed advantage and an enormous 20 per cent working memory advantage in the face of mental stress. But the real intrigue lies in the detail beneath the headline figures.

Among the racers, Oli Webb emerged with the best overall performance in the working memory test, scoring 97.5 per cent accuracy under both positive and negative stimuli. According to Professor Walsh, this suggests that he is “undisturbed” by stressful events, an observation that holds up given that his reaction times remain largely unchanged throughout.

Compare that to Colin Turkington, who under stress was 36.25 per cent worse off in terms of accuracy and slower to react in all conditions. But far from being a weakness, it could just be that his scores are a product of being a touring car driver: with such short races there is much less emphasis on retaining information than there is in endurance racing.

Fascinating though that is, it’s the showing of John McGuinness that really stands out. By far the most accurate athlete in the visual recognition section of the study, the TT rider’s overall results demonstrate two remarkable qualities.

The first is a tendency to lift performance when exposed to the negative influence: where the non-athletes crumbled in the face of fear, McGuinness was consistently able to raise his game.

The second is an ability to rapidly recover and regain composure following dips in performance, a trait few of the other athletes could match to his level.

And all this from a man in his mid-forties. “That really shouldn’t happen!” exclaims Walsh.

We might have more gains from this deeper psychological understanding of what it means to be under pressure.

With the athletes’ dominance firmly established, the question of why their brains function better remains to be answered.

“I think it’s the training,” reasons Walsh. “It can’t possibly be the case that the handful of boys each year whose parents can afford to get them into karting happen to be the people who are genetically selected to do motorsport.

“And the good news about that is that the rest of us can get better as well. Possibly even more so, because these guys are starting from a higher baseline. So we might have more gains from this deeper psychological understanding of what it means to be under pressure.”

For the rest of us in the real world, it should be a comfort to know that the key to overcoming life’s everyday struggles lies within. How to go about unlocking that potential is another matter, though as American philosopher Will Durant once said: “We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act but a habit.”

If you’re in need of inspiration look no further than Nico Rosberg, for whom perseverance was the gateway to the realisation of his dreams. Having outlasted 18 years of disappointment, he is now the master of his fate. He is, at last, the captain of his soul.

Trending this week

- Car Review

BMW iX3