Recreating The Italian Job in a Lamborghini Miura

In 2016, we celebrated the original supercar’s 50th birthday with a drive to remember

Once. Just once. That’s how many times Italian designer Marcello Gandini has drawn the scintillating silhouette of what we now know as the Lamborghini Miura.

As a 27-year-old in 1965, he didn’t need any more attempts; he knew he’d nailed it. His stylish squiggle was perfect. And he’s never drawn it since. Even when I thrust a pen and paper his way, not wanting to ruin the masterpiece, or succumb to failure, he flat out refuses to have another go at replicating the famous shape.

Words: Rowan Horncastle

To be fair, you don’t see golfers teeing up to have another go at a hole-in-one, do you?

The profile he’d created was so elegant and purposeful, that if a six-inch stiletto heel was under it, every woman would want to wear it. Thankfully, it wasn’t destined for feet. Instead, a group of young, enthusiastic and revolutionary engineers placed it over an Avant-garde chassis with a transverse V12 in the middle, stuck four equally-sized fat wheels at each corner and birthed the world’s first supercar.

Shown publically to a slack-jawed audience in 1966, it captivated a generation. Then kept people interested. It's timeless. A classic. An icon. A legend. The Miura has had all the compliments thrown at it over the years, yet shrugs them off without a whiff of arrogance.

It’s also turning fifty this year, meaning a celebration is in order. But, being such a special car, it deserves a little more than a Caterpillar Cake and a kazoo posted to Sant’Agata Bolognese to mark the momentous half-century.

That’s why I’m currently at the bottom of an alp, perched on a concrete guardrail looking up at seemingly endless swirls of black tarmac piped up the side of it. It’s the Great St Bernard Pass, a fabulous driving road made famous in the opening sequence of The Italian Job when a bright orange Miura speared across the landscape to the sounds of Matt Monro’s ‘On Days Like These’.

If you’re too young to remember the film (don’t bother with the rubbish American remake, kids), check out the first five minutes on YouTube. It’s a refreshingly simple recipe – amazing car, fantastic location, simple camerawork mixed with a great soundtrack – that gets your imagination and interest salivating.

Everyone wants to be that man sat behind the wheel; shades wrapped around your face, cigarette in mouth, winding your way around the mountain in one of the coolest cars in the history of ever. Well, today I’m attempting to be that man. Gulp.

Sitting effortlessly ahead of me is a glinting gold Miura S. It’s gorgeous.

Sitting effortlessly ahead of me is a glinting gold Miura S. It’s gorgeous. The curvaceous, sweeping hips and infamous eyelash headlights are incredibly feminine yet it’s far from dainty. Bettering the looks are its proportions. They are absolutely on point. Not bad for an out-of-hours skunk works project by a bunch of blokes in their twenties, eh?

Top Gear

Newsletter

Thank you for subscribing to our newsletter. Look out for your regular round-up of news, reviews and offers in your inbox.

Get all the latest news, reviews and exclusives, direct to your inbox.

See, the Miura is very much a product of its time. Having successfully taken the fight to Ferrari and Maserati with the 350 GT, Ferruccio Lamborghini wanted to intensify the Modena turf war and block out the haters with something new and radical.

Being open-minded, Ferruccio tasked chassis wizard Gian Paolo Dallara and his fresh-out-of-uni engineering understudy Paolo Stanzani to develop a new super Lambo.

“Nothing was off the cards,” Dallara tells me. “Ferruccio wanted to step away from the norm. He wanted new technologies: independent suspension, a different gearbox and engine configuration. But he also accepted our limited experience in what was effectively a start-up company, so was quite forgiving if it went wrong.”

There was only one stipulation: it couldn’t go racing. In his own words, Ferruccio believed there were better ways to pour money down the drain than lapping tracks. But that didn’t stop Dallara using motorsport as inspiration.

Enamoured by Ford’s GT40 – notably the mid-engine layout – Dallara and Stanzani wanted to break convention and cook up an exotic GT with a monster V12 engine behind the driver’s head, rather than at the end of their noses.

The problem was getting the honking engine to fit within the chassis length. So, instead of mounting the engine in the traditional way (longitudinally), Dallara flipped it 90 degrees and threw it in horizontally – or, transversely, if you want to give it its proper name.

Then, by nicking a trick from the Mini, he and Stanzani conjoined the aluminium cylinder block, crankcase and transmission housing into one almighty mechanical Megazord to better the centre of gravity.

“We knew it was something revolutionary,” Stanzani says. “As each day we were scratching our heads more and more trying to overcome problems.”

Like having to reverse the direction of the crankshaft, or working out how to get all the oils to work harmoniously in the fused engine-transmission combo behind the driver’s noggin. But they did. And showcased a bare chassis at the Turin Motor Show in November 1965.

Each day we were scratching our heads more and more trying to overcome problems.

Even though it was naked, the technical architecture of the ‘P400’ (as it was then known) shocked everyone. It arrived with intent. Having only been operating for a year, Lamborghini didn’t have the time, money or scale to mess about with concepts. The Turin show was a market stall for new business, and there was one job at hand: finding someone to dress the chassis with a beautiful body.

See, in-house design studios weren’t a thing in the swinging Sixties like they are now. Back then, you’d build a chassis and let various coachbuilders fight over designing body panels for it. Ferruccio wanted fresh blood to go with his cutting-edge chassis and saw Touring (Lambo’s go-to guys) as too traditional for the project. Pininfarina? They were aligned with Ferrari, so a no-go. But Ferruccio had one name in mind: Bertone.

With the motor show doors about to close, Nuccio Bertone approached Ferruccio and a deal was done. He assigned design newbie Marcello Gandini with the gig, who started sharpening his pencils right away.

In the same way modern in-house design studios didn’t exist, neither did R&D departments. The R&D office for the Miura was the local bar, with focus groups consisting of the drunken alter egos of the handful of guys working on the project.

The Miura’s founding fathers – Gandini, Dallara, Stanzani and Kiwi development driver Bob Wallace – thrashed out ideas to get the P400 on the road. Enthused and excited by the opportunity to crack their knuckles and show what they’d got, they worked tirelessly on it.

This mentality, plus the openness, skillsets and flexibility of the team created a car that was a perfect storm of sorts. The packaging allowed for a new chassis, giving way to the unique engine and gearbox placement, which allowed for Gandini’s silhouette to be smoothly draped over it in less than a month.

Body and running gear complete, there was only one job left to do: christen it.

The Miura started the now famous nomenclature of Lamborghinis being named after famous breeds of bulls or bullfighting jargon. Settling for Miura, (fighting bulls, bred in Seville by Don Eduardo Miura) the name was sealed with a mischievous and childish doodle of a logo on the back by Pierro Stroppa. Still one of the coolest logos to ever be stamped onto the rear of a car.

It was shown at Geneva a few months later, and was an instant hit. It was a zeitgeist car and celebrity must-have accessory; Frank Sinatra, Little Tony, Rod Stewart, Twiggy, Miles Davis (who famously broke both legs after crashing his with two suspicious bags of white powder in the front seat) all had to have one. But it was its casting in The Italian Job that gave the Miura real gravitas and reach with the general public.

It was a zeitgeist car and celebrity must-have accessory; Frank Sinatra, Little Tony, Rod Stewart, Twiggy, Miles Davis all had to have one.

For anyone who’s seen it, you may remember that the drive doesn’t end tremendously well. Having entered a tunnel, the Miura goes headfirst into a strategically placed bulldozer left by the Mafia. It’s then dragged out into daylight and thrown off the side off the mountain.

Now, don’t get me wrong. I want to be as true to the original as I can, but I don’t want that to happen. Although… it is a good excuse if things do go a bit pear-shaped.

Clinking the door release button, I grab the vented door pillar (designed so when both are open to look like a bull’s horns) and pull the aperture wide open. A belch of the interior’s aroma – tired leather, fuel and oil – wafts up my nostrils. Lovely.

Overcome with character, I just need to work out the angle of approach to get in the thing. To give you a sense of scale, the rear of the car comes up to the top of my shin while the roofline is lower than my waist. Being gangly, this ain’t easy.

First step, right leg over the air-robbing rocker vent and into the footwell. Next, a sort of shimmy-limbo-thing down to seat level, and then a sideways hop into the recessed cabin. I’m sure Twiggy did it with a hell of a lot more grace.

The driving position is, err, interesting. If you’re a fully-grown adult and would like to experience it for yourself, try and get into one of those coin-operated kids ride-ons outside supermarkets. Your legs are splayed, knees bent, and have to fumble your legs under the steering wheel to reach the correct pedals. Strangely, they’re placement isn’t as drunk as later Italian supercars, just far forward and set vertically.

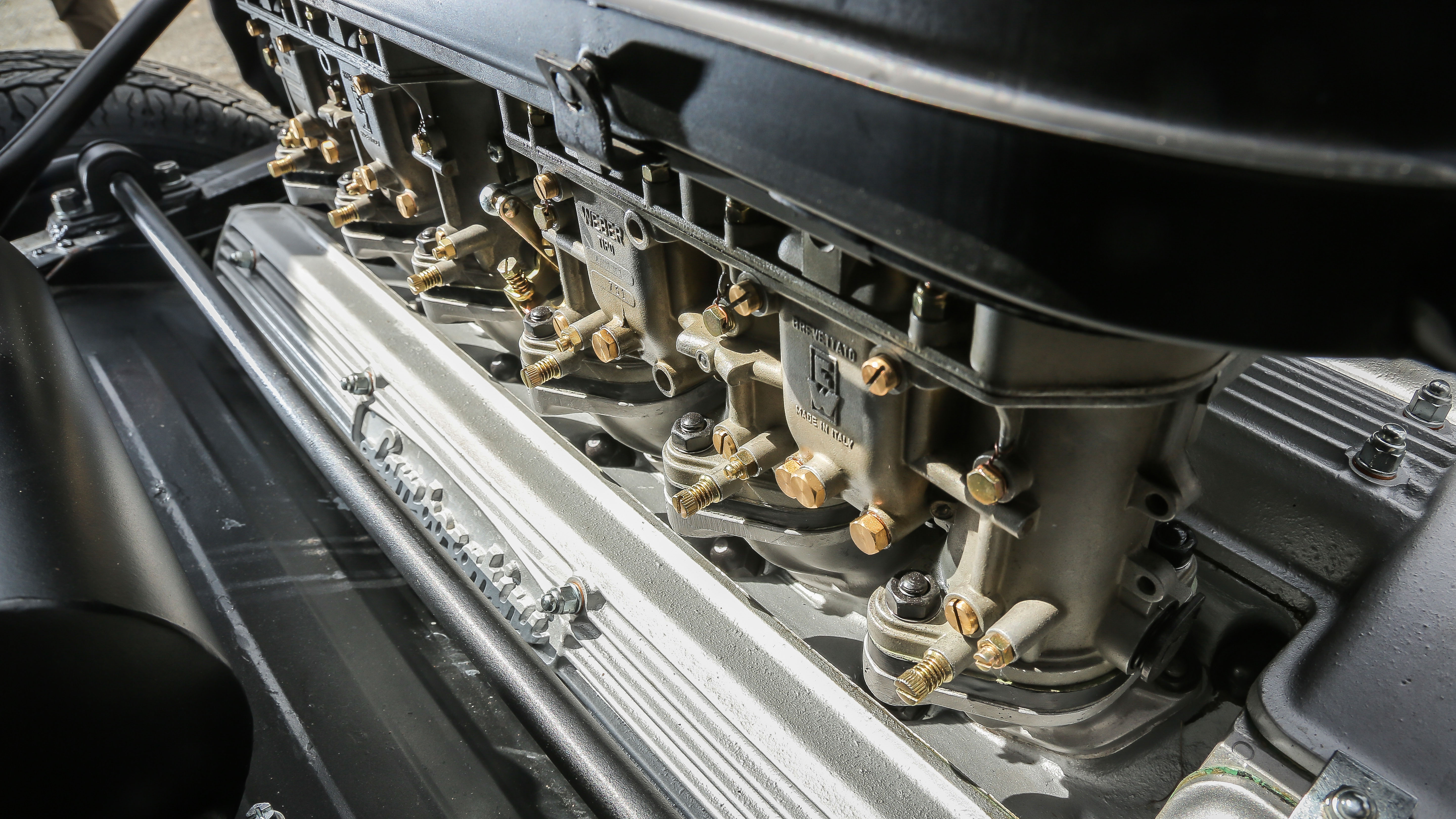

The cabin is special. Dead ahead, a minimalist drilled steering wheel that watch manufacturers constantly try – but fail – to mimic. Behind it, two big minimalist clocks dominating the space. Down to the right, a manual gearlever; five-speed, with an open gate. Oh yes. Above that, a bank of six Jaeger dials canted towards the driver. Behind, the 3.9-litre V12 squished right against the glass like a commuter’s cheek on a packed train.

Key in the ignition, I tickle the throttle and nervously twist the barrel. With four triple-barrel Weber carburettors, notoriously leaky plumbing and a hot engine just below to ignite it all, self-immolation is well documented in Miura ownership. “Not today, please” I whisper under my breath as I pump the throttle harder and fire into life.

Now, what you don’t see in The Italian Job is a three-point turn. That’s because it’s an incredibly ungracious procedure. At standstill, the steering requires Maximuscle sponsorship if you want to go from lock-to-lock, while shifting from reverse to first is a hefty two-handed operation needing the strength and motion normally only reserved for an old train signal box.

Enough of the fundamentals, time for an ascent. Having had a kind word with the Italian constabulary, they’ve very kindly closed the road meaning; one, there’s no oncoming traffic. And two, I can go as fast as I see fit.

Chin raised to snoop over the long aluminium bonnet, I pull out to begin a very quick orientation process of someone else’s very expensive 50-year-old supercar.

The clutch is heavy but manageable, throttle long and lubricated with treacle but the visibility from wrap around glass and pencil-thin A-pillars is fantastic. Brakes? A test stab reveals nothing. A significant prod… still nothing. I make a mental not to do as much braking off the engine as I can on the way down – especially as there are no seatbelts and colossal drops either side.

Here comes the honesty. I was expecting the Miura to drive like an absolute pig. The thing is, it really doesn’t. Well, as long as you’re not at slow speeds. It’s one of the most willing cars to be flogged I’ve ever driven. Clacking through the gears it actively wills you on for more throttle. And boy does it start to lay on the charm when you grant its wishes.

Easing out the throttle to ‘Leg Straight’ levels, the 12-cylinder, 370bhp engine harrumphs its way through the bottom end of the rev range before angrily thumping and gurning nearer the top before singing sweetly.

As you push on the steering becomes light and useable. It lacks deftness but you know where you’re at with it. As I climb and climb I increase the speed, threading through the winding esses, double de-clutching through the hairpins and revelling in the unburnt fuel gargling from the protruding exhausts on the overrun.

Back in the day, the Miura was another level quick. 0-60mph was seen off in 6.7 seconds, while it’d romp on to a crazy 172mph. For context, the best-selling car at the time – the Austin 1100 – had a sketchy top speed of 87mph and 0-60 time of 17.3 seconds. The Miura was the Millennium Falcon… if it’d been invented, that is.

Today it doesn't feel slow. But better than that, unlike modern supercars, the engine and gearing mean you get to go through the full firework show of dramatics of revving out the V12 fully for the first three cogs and remain at a manageable but quick speed without wanting more. You're satisfied. If you do go faster you have to lean more heavily on the brakes. Something I’m not brave enough to test comprehensively.

Climbing higher and higher the air gets thinner and crisper. Greenery turns to greyscale as ruffled snow banks line the side of the road. Looking back through the rear view mirror and peering through the famed Venetian blind rear louvres, the snaking dry tarmac falls away into the horizon.

“What a road!” I can’t help but yelp. Winding, blind bends are blinkered by rock piles on one side and half exposed concrete guards to the other. It’s exciting and challenging. Further up the melting snow begins to lubricate parts of the pass. I settle down to a cruise, put Matt Monro on Spotify (cliché I know but you have to) and soak up the magic.

The Miura was the original mad Italian supercar. It’s ingenuity and against-the-grain thinking has been copied by others since, but fundamentally it laid the foundations for the Countach, Diablo, Murcielago and Aventador. They’re all big V12 brutes that have been plastered over bedroom walls and mesmerised petrolheads around the world for half a century. And we have this car and a bunch of alterative-thinking twenty somethings to thank for it.

So happy birthday, Miura. The times are-a-changing, but here’s to another fifty years of crazy Lamborghinis.

More from Top Gear

Trending this week

- Car Review

BMW iX3